"Is Stalin a man of genius, or not?"

The reply that came during a seance, according to a defendant's testimony given at a Kyiv court on March 10, 1948, was that the Soviet dictator was no such thing.

Coming at a time when Josef Stalin's cult of personality was at its height, such a conversation was sure to attract attention. Especially because the founding father of the Soviet Union, Vladimir Lenin, was allegedly the one replying from beyond the grave during the conjuring, more than two decades after his death.

Other court evidence revealed that during one of the seances "Lenin" predicted from the afterlife that war was coming -- six countries would soon free the Soviet people from Stalin's yoke.

When asked about the future of Soviet power, an unidentified Russian revolutionary responded that "it won't exist, with the help of America."

Such "conversations" were revealed in archived documents of trial testimony and interrogations carried out by the Soviet State Security Ministry (MGB), which included the secret police.

Aside from Lenin, the court heard from a number of early Soviet A-listers, some of whom might have cause to slander Stalin.

There was archrival Leon Trotsky, who was assassinated in Mexico City in 1940 on the Soviet leader's orders. And Nadezhda Alliluyeva, Stalin's second wife, who died under mysterious circumstances after a public argument with her husband in 1932.

Others speaking from the grave included the writers Maxim Gorky and Aleksandr Kuprin, as well as famed rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

Their questioners were not members of the Bolshevik inner circle, but ordinary residents of the north-central Ukrainian town of Bila Tserkva who had never even belonged to the Communist Party.

For their role in conjuring up voices from the past, Ilya Gorban, his sister Vera Sorokina, and his lover Olga Rozova were arrested and accused of anti-Soviet acts and the "creation of an illegal religious-mystical group of spiritists."

Wandering Soul

Gorban was an unaccomplished artist when he moved to Bila Tserkva from Kyiv in early 1947, a year before the trial.

The 44-year-old native of the Poltava region had designed museum exhibits and prepared posters and portraits of Lenin for demonstrations. He was wounded during World War II while manning an anti-tank gun near Oryol.

He had married and fathered a child. But the marriage ended in divorce and his daughter lived with her mother.

Gorban settled into his new life in Bila Tserkva with his sister, Vera, and got a job at the local industrial plant as a sculptor.

A book lover, he frequented the city library and soon entered into a romance with 39-year-old Olga Rozova, a library employee.

Rozova was married. But her husband -- Andrei Rozov, a journalist with a newspaper in Voronezh -- had been accused of belonging to an "anti-Soviet Trotskyite terrorist organization" in 1938 and imprisoned for 10 years.

While at work, Gorban had a conversation with colleague Mikhail Ryabinin, who asked the sculptor if he believed in the afterlife and the existence of spirits.

Gorban said he did not, but he did take Ryabinin up on his recommendation that he read the Spirits Book -- written in 1856 by Frenchman Hippolyte Leon Denizard Rivail under the pen name Allan Kardec and considered one of the pillars of spiritism.

Pointed 'Discussions'

The doctrine of spiritism, or Kardecism, centers on the belief that the spirits of the dead survive beyond mortal life and can communicate with the living. The communication usually takes place during seances conducted by a person serving as a medium between this world and the otherworld.

Gorban read it with fascination and proposed that Ryabinin organize a seance. His friend declined, however, saying according to case files that "all these sessions with plates -- they are nonsense and baby talk. I contact the spirits at a higher level."

Gorban's sister agreed to try, however, and together they conducted a seance based on what they had learned.

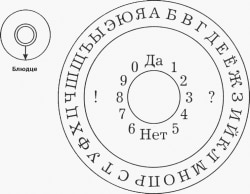

They lit candles and sat at a table with a sheet of paper in the center. On the paper the letters of the alphabet, the numbers zero through nine, and the words "yes" and "no" were drawn in a circle.

A saucer with an arrow from the center to the edge was set over the paper.

The idea was to call on the spirits of a particular person and, if he or she appeared, to ask them questions. If all went well the saucer, beneath the hands of participants, would begin to rotate freely and without force, spelling out answers by pointing to the appropriate symbols on the paper.

Family Affair

Altogether, Gorban and his sister conducted 15 to 20 seances in the summer and autumn of 1947. At times they reached out to people outside the Soviet circle. The spirits of deceased relatives were often conjured up, including the siblings' mother, who allegedly gave the pair everyday advice. They even got a hold of Alexander Pushkin, but the Russian poet "cursed" them.

Gorban's girlfriend, Olga Rozova, began to join the sessions, and the group conjured up a late writer who began to compliment her.

"I suspected that this was a trick of Gorban's, with whom I had been in an intimate relationship," she recalled during her courtroom interrogation. "The whole session was of a purely personal, amorous character."

Some sessions were held at Rozova's apartment, which was inside the library. A friend of hers who headed the local school library, Varvara Shelest, took an interest and also started attending the sessions.

The last seance, according to testimony of group members, was held in December 1947.

They asked Lenin's spirit about the monetary reforms enacted that year, which included the denomination of the ruble and the confiscation of personal savings.

Knock On The Door

A couple of months later, Chekists -- agents of the feared secret service -- came for them.

Rozova was detained on February 19, 1948; Sorokina and Gorban were taken away the next day.

The case was transferred to the authorities in Kyiv, and the trial began on March 6, just two weeks after the suspects were detained.

From the MGB's point of view, the seances were evidence of the formation of an "illegal religious-mystical group" -- which on its own could have led to imprisonment. But the authorities took things one step further by adding the more serious "anti-Soviet" charge.

"This seance had a sharply anti-Soviet character," read one file. "This deliberate slander pertained to one of the leaders of the [Communist] Party and government."

When initially questioned, the three did not appear to hide that they had participated in seances. Gorban and Sorokina wrote them off as an attempt to have fun; Rozova said there was no intended goal.

But ultimately their confessions were recorded by their interrogators -- the sessions were driven by anti-Soviet sentiment and were just a "convenient screen" for "slanderous agitation."

In his interrogation report, Gorban was quoted as saying he had "tried to defame and slander the Soviet powers and the leaders of the Party and government" to expose the "talentlessness" of Soviet leaders to his alleged accomplices.

Disgruntled by postwar poverty, it was Gorban who had directed the movements of the saucer, according to the documents.

Harsh Ruling

During their trial, those alleged admissions were recanted. Each of the three defendants declared that they did not believe in the otherworld or spirits. When queried about their religious beliefs, each answered that they were atheists. And their sessions, they said, were for entertainment.

"I didn't think that our sessions were anti-Soviet," Sorokina testified. "What we did was, of course, not good, but I was, am, and will remain a Soviet person."

As for the saucer, Gorban said, he had no idea how it moved. All admitted to partial guilt, according to the court files.

The ruling in their case came on March 10, after just two court sessions.

The three were found guilty of anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation, and of participation in a counterrevolutionary organization.

Gorban was sentenced to 25 years in a labor camp; Rozova and Sorokina to 10 years each. Gorban would have been executed had the verdict come a year earlier -- but the death penalty had recently been suspended.

The Mystery Of 'North'

The role of Gorban's colleague in all this was not forgotten. A criminal case was opened against Ryabinin -- the man who had suggested Gorban read the Spirits Book -- the same day the others were sentenced.

It is unclear, however, what might have happened to him.

Rozova's friend, Shelest, also remains a mystery. Despite her attendance at the group's seances, she was apparently never detained.

According to the case files, she disappeared shortly after the others were nabbed. Material related to her was transferred to a different case, a common step intended to avoid the search for the accused slowing down the investigations of those detained.

When it later emerged that the others had been arrested as part of an underground sting operation, Shelest's name was not listed among the targets. And when the MGB informed other Soviet authorities about the eradication of a group of spiritists in Bila Tserkva, it made mention only of an informant -- codenamed "Sever" (North) -- who had attended some of the sessions.

But Shelest's name did pop up. During their trial the three defendants claimed it was Shelest who initiated most of the "political" questions posed to spirits -- including Trotsky, Alliluyeva, and Gorky. Rozova said she had suspicions that Shelest had manipulated the saucer's movements.

In requesting a pardon in 1954, one year after Stalin's death, Rozova wrote that "at the trial it became clear to me that Shelest had been tasked with creating an anti-Soviet crime from our seances." She further argued that Shelest continued to live in Bila Tserkva, yet no one was trying to question her.

Around the same time a prosecutor wrote that while Sorokina and Rozova were "addicted to spiritism because of their curiosity and irresponsibility," their actions did not result in serious consequences. The two, the prosecutor argued, should be released.

The Supreme Court eventually ruled that while the verdicts handed down against Gorban, Sorokina, and Rozova were correct, their sentences were too harsh.

Sorokina and Rozova were released on February 22, 1955, seven years after their arrest. The decision came too late for Gorban, who died in 1950 while incarcerated at a labor camp near the Arctic Circle.

In 1992 -- less than one year after the dissolution of the Soviet Union -- all three were rehabilitated.