With its vast oil and natural gas resources and centralized rule, Kazakhstan might appear, at first glance, to have no qualms about stability. But protests by hundreds of outraged women demanding a reform of the country’s social-benefits system have underlined potential vulnerabilities, observers say.

The protests kicked off in Astana, the Kazakh capital, immediately following the February 5 funeral of five girls, between 3 months and 12 years old, who had died in a house fire while their parents were away working. By late February, rallies of mothers urging the government to help other such low-income families had spread to the cities of Almaty, Aktobe, Karaganda, and Shymkent.

The women’s demands included social housing, more public kindergartens, and higher social-welfare payments for children.

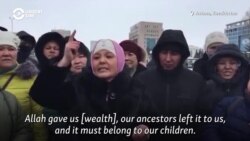

“They say we have a rich country! Allah gave us [wealth], our ancestors left it to us, and it must belong to our children. Our children should [get] it! Why should we live in poverty?” asked Kunsulu Iskakova, a participant in a mothers’ rally in Astana.

Tragedies like the Astana fire can happen again since many families cannot afford adequate housing, protesters emphasized. The demonstrations continued despite the authorities’ February 18 announcement that a new program would be developed to help families with multiple children rent apartments.

In response, Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev went one step further.

On February 21, Nazarbayev asked the government to resign for failing to improve the living standards of these families with multiple children.

Roughly a week later, Nazarbayev announced a $5.3-billion (2-trillion-tenge) basket of increases in various forms of social-welfare payments and support, including the construction of 40,000 apartments, primarily for families with multiple children. The increases would take place by 2022.

But some observers question whether such massive payouts will have much long-term effect.

“Even if they allocate large amounts of money for apartments or offer some good government programs, it still won’t solve the problems,” commented human-rights activist Galym Ageleuov, president of the non-profit Liberty Foundation, in an interview with Current Time Evening.

While Kazakhstan’s official unemployment rate has been steadily decreasing (to 4.8% in 2018), Ageleouv asserted that the government’s role in Kazakhstan’s energy-dependent economy has squeezed out private and small business owners. At the same time, no space is given to ordinary citizens to discuss needed core political reforms, he charged.

Against that backdrop, even non-political protests like the mothers’ demonstrations “have this potential of turning into political opposition, political resistance as well, depending on how the government responds,” noted Erica Marat, chair of the National Defense University’s Regional and Analytical Studies Department, in RFE/RL’s March 3 Majlis podcast.

Violent crackdowns against protesters could amplify that potential, she predicted.

“The government has avoided doing exactly that with the mothers, but who knows what other collective action will be in the coming months and years … ”

Human-rights activist and journalist Sergei Duvanov contended that the brusque breakup of national protests in late February for broader social-welfare benefits suggests that the government will now act to stamp out any form of public demonstration.

Officials, however, reject any criticism of the government's stance on civil rights.

-- Text by Diana Jacobs

Facebook Forum