Amidst a court fight over whether or not jailed opposition leader Aleksei Navalny’s offices and organizations should be banned as “extremist,” the Russian government is attempting to promote a Russian video-hosting service as an “alternative” to YouTube, a U.S. video-sharing platform that has brought the Navalny movement’s exposes on alleged government corruption to tens of millions of viewers.

With Russians scheduled to vote in parliamentary elections on September 19, 2021, the outcome of that campaign could prove critical. Navalny’s operations rely heavily on social media like YouTube to reach supporters. If prosecutors convince the Moscow City Court that the politician’s regional offices, Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), and Citizens’ Rights Protection Foundation (FZPG) acted as “extremists” and attempted to foster rebellion, their posting content on YouTube will be illegal under Russian law.

Already, the offices (closed as of April 29), the FBK, and the FZPG all reportedly face temporary restrictions on posting material online until the release of a verdict. Deliberations started on April 29.

Nonetheless, the so-called “Navalny effect” is continuing on YouTube.

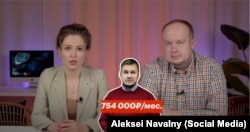

On April 28, two FBK investigators, Maria Pevchikh and Georgy Alburov, released a new YouTube video on Navalny’s YouTube channel that targeted the hefty salaries paid by the state-funded international broadcaster RT to personalities who create content that lambasts the Russian opposition. Within roughly 24 hours, the report had attracted over 2.3 million views.

A January 2021 FBK documentary on a luxurious Black Sea mansion allegedly owned by Russian President Vladimir Putin that received 116 million views encouraged some Russians to join unauthorized protests for Navalny’s release from prison.

Such a reception could have contributed to the decision to place temporary restrictions on Navalny activists’ ability to post online material, believes political analyst Andrei Kolesnikkov. In the long term this election year, however, it could lead to further measures, he said.

“When a third of the country’s population watches the film, of course, this isn’t pleasant, and the authorities want to regulate this process somehow – and, even better, to stop it,” Kolesnikov said.

Enter Rutube, a video-hosting service that has existed since 2006, but without gaining substantial traction among Russian users. Dubbed “the Russian YouTube,” the platform offers some 3 million videos, including podcasts, entertainment and news videos, as well as games and live streams. Earning ad revenue is reportedly an option.

In late 2020, as media regulator Roskomnadzor urged Russia’s “leading Internet companies” to create and popularize Russian video-hosting services, Gazprom Media, the country’s largest media company and part of state-controlled energy giant Gazprom’s business empire, acquired Rutube.

At the same time, Roskomnadzor began to complain actively to YouTube about what it considered to be discrimination against news from Russia’s state media outlets in the platform’s search results. Public discussion surfaced about a potential ban, a threat later used against Twitter.

Billions of rubles have been invested into state-run Russian television, but with relatively modest results on YouTube. RT, for instance, has 4.23 million subscribers, versus Navalny’s 6.51 million.Its top 2021 documentary, about the Klu Klux Klan, has received just 136,000 views.

Under Russian law, any case of online discrimination against state media can be met with a partial or full blockage of the offending site, plus administrative fines.

YouTube has denied any such discrimination, stating that algorithms determine content popularity.

But, now, following a relaunch of Rutube in early April, Moscow believes it also has a platform of its own with which to respond – one that plays by Russian rules.

Unlike “famous American platforms,” Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova stated at an April 9 briefing, Rutube “will remain free from censorship by IT monopolists, tampering with search requests and non-transparent algorithms.”

Rutube General Director Roman Maksimov, however, prefers to call the service “an alternative platform” to YouTube, rather than a “competitor.”

“There’s no assignment to hurt someone,” Maksimov commented to Current Time. “We’re a Russian company, we work according to Russian laws, and we obey Russian norms.”

Some critics fear that means censorship. In early April, Rutube moderators blocked Open Media, a news site financed by expat Kremlin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky, from uploading FBK’s documentary about “Putin’s palace.”

According to Maksimov, though, the reason was simple: “Because in Russia we have a law on ‘foreign agents.’”

Under that law, government-listed “foreign agents” – foreign-financed organizations or individuals involved in “political activity” – must label their content with a tag that acknowledges that status. Though the FBK ranks as a “foreign agent,” its documentary does not carry the label. *

“By law, we can’t let such content out onto the Internet,” said Maksimov. “If it had been titled, it would have gotten through moderation” and been posted, he claimed.

The first two results for a search query of “Navalny” on Rutube, however, only show commentary by film-and-video translator Dmitry Puchkov and a promo for a channel, Taxi Style, about “work in a Moscow taxi.”

Ranked third is an April 8, 2012 interview by Ekho Moskvy (Echo of Moscow), a radio station owned by Gazprom-Media, with a neurosurgeon about Navalny’s state of health.

Gauging this content’s appeal is not possible: Unlike YouTube, the hosting service does not show the number of views for posted videos. The site also provides no information about its total number of registered subscribers.

One popular Russian blogger on YouTube, however, doubts that Russian users will ever make the switch from YouTube to Rutube.

“Rutube, unfortunately, is an old dinosaur that has many problems, even if they’re now trying to refresh it,” said Valentin Petukhov, known as Wyslacom. “There’s not a single reason why I would need to go to Rutube,” he said. The service, he claims, lacks exclusives, “content,” and any proprietory material from Gazprom-Media.

Political analyst Maksim Zharov, a former Kremlin aide who has written on Russia’s cyber-strategy, objected that neither Gazprom-Media, nor Roskomnadzor pay attention to complaints about sluggish video-upload times. That will not encourage migration to Rutube, he said.

“This way, of course, no one will go anywhere. Without work, you can't catch a fish out of a pond.” Zharov commented to Nakanune.ru.

At least half of all Russians between 18 and 24 use YouTube daily, according to a Statista.com analysis. It currently ranks as the most-watched video platform in Russia.

YouTube has not commented how it will respond if Navalny and his organizations are classified as “extremist.” Its guidelines ban “violent extremism” and hate speech, but nothing related to Moscow prosecutors’ charge about attempting “a color revolution.”

The site has, however, previously responded to Roskomnadzor complaints by removing some offending content.

But even if shut out of YouTube and other social media, Navalny and his colleagues will not disappear from Russia’s public life, believes analyst Kolesnikov.

“Somehow,” he said on April 26,, “the Navalny team, obviously, will find some other workarounds in order to show their investigations, make announcements about themselves and their events."

*Current Time TV, led by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in cooperation with Voice of America, also has been listed as a "foreign agent."

-This story used additional reporting by bneIntelliNews, Reuters, and TASS