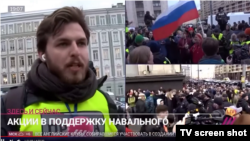

Multiple detentions of journalists in Moscow following the unauthorized, April 21 protest in support of jailed Kremlin critic Aleksei Navalny are prompting concerns that city police are using the Russian capital’s tens of thousands of surveillance cameras to intimidate media.

The measures coincide with prosecutors and the Moscow City Court suspending the activities of Navalny’s regional offices, Anti-Corruption Foundation, and Citizens' Rights Defense Foundation, pending a ruling on whether or not these groups are “extremist.”

Officials previously have used footage from surveillance cameras to track down alleged participants in unsanctioned pro-Navalny rallies, but the technology this time appears to have been used to justify interrogations of journalists from Russian-language news outlets that question government policies.

Officially, however, Moscow’s network of “more than 204,000” surveillance cameras exists to improve the “quality of life” and “level of security” of the city’s roughly 12.7 million residents.

But for Aleksei Korostelyov, a reporter for the independent TV station Dozhd (Rain), the cameras’ benefits have been few.

On April 27, police brought Korostelyov in for questioning about his alleged participation in the April 21 protests for Navalny to receive non-prison medical care and to be released from prison. Participation in a public gathering unsanctioned by city authorities is an administrative offense under Russian law.

To justify their actions, officers showed Korostelyov a small fragment of protest footage from a surveillance camera that showed a young man in a black hoodie who resembled him, he told Current Time. Korostelyov denied that it was him.

During the April 21 protest, the reporter had been shown on air wearing a yellow vest marked Press, as required by the government’s media-regulatory agency, Roskomnadzor. He also was carrying an accreditation card and information about his editorial assignment – two other requirements.

But that, apparently, made little difference. A police inspector showed Korostelyov a video of the journalist in the yellow vest, yet noted that the vest can be bought in a store. He added that it is “easy to forge the press card,” Korostelyov said.

Korostelyov was released and not charged, but had to sign a pledge that he would return to the police on April 30.

Other reported cases generally follow the same pattern: Since April 26, police have also visited the homes of Ekho Moskvy (Echo of Moscow) radio station reporter Oleg Ovcharenko, Meduza special correspondent Kristina Safonova, RFE/RL Russian Service correspondent Anton Sergienko, Komsomolskaya Pravda journalist Aleksandr Rogoza, and TV channel RTVI’s photo editor Ivan Krasnov. All have been requested to prove their journalist credentials, and some to appear again before police.

“[T]his is, of course, first of all, a story about technologies,” commented Komsomolskaya Pravda war correspondent Aleksandr Kots, who posted on Telegram about his colleague’s detention. “The future is already here.”

Some observers hold that it is also a story about the risks independent media face in Russia, whether covering Navalny or other government critics.

On April 26, a journalist for the Volnitsa news agency, Yelizaveta Loshak, was detained while covering an unauthorized Libertarian Party rally near Russian government headquarters. Loshak was fined 200,000 rubles ($2,676) for supposedly violating the regulations for organizing a public event.

Why police considered Loshak an organizer was not immediately clear.

An online campaign by Volnitsa raised money for the fine, but the news agency does not believe the police intervention bodes well for the future.

“Today, once again, we became witnesses of judicial arbitrariness against journalists,” Volnitsa tweeted on April 27. “It’ll get worse.”

Foreign media organizations have not avoided this police scrutiny.

On the evening of April 28, photographer Georgy Malets from Belsat, a Poland-based media organization long prosecuted by the Belarusian government, a strategic Russian ally, was brought in for questioning about the Navalny rally, reported MBKh Media. A criminal investigations officer reportedly made up the detail.

Malets, detained for similar reasons in January, insists he had only covered the protest as an accredited photojournalist. He tweeted that the police said they did not know that he was a journalist.

Police also have targeted at least two journalists from so-called “foreign agents” – alleged recipients of foreign funding whom the Justice Ministry considers to be involved in “political activity.”

In Meduza correspondent Safonova’s case, after giving police the “necessary documents” to prove her identity, the Molzhaninovsky district police station informed her that they intended to file administrative charges against her for supposedly violating the law “for organizing and holding a public event,” Meduza reported on April 28. The outlet did not elaborate about the grounds for this charge.

Four days earlier, Meduza, a for-profit, Russian-language news site in Riga, Latvia, was designated as a “foreign agent.” In an interview with Current Time on April 26, Meduza Editor-in-Chief Ivan Kolpakov called the label “a political decision” intended to make the outlet “drop dead” from potential loss of advertising.

On April 26, police targeted a correspondent from another so-called “foreign agent,” RFE/RL, also for supposedly participating in the April 21 Navalny rally. (RFE/RL runs Current Time in association with the Voice of America.)

Anton Sergienko posted on Facebook that the police, who questioned him for two hours, “knew that I’m a journalist” and later “excused themselves” for taking him in for questioning, but he underlined that this does not excuse their behavior. He claimed that the police who came to his residence had “kicked in” the vestibule door, mentioned a criminal investigation, and alarmed his neighbors.

Their questioning occurred four days after RFE/RL’s Russian Service posted a video shot by Sergienko that shows a suspected police “provocation” at the April 21 Navalny rally.

As yet, the government’s response to these detentions, a fraction of some 58 estimated post-rally detentions in Moscow, is limited.

Responding to public inquiries, an aide to President Vladimir Putin, Vadim Fadeyev, head of the Presidential Council on Human Rights, requested the Interior Ministry on April 28 to provide an explanation for the detentions of Dozhd’s Korostelyov, Ekho Moskvy’s Ovcharenko, and Komsomolskaya Pravda’s Rogoza.

As of late April 28, the ministry did not appear to have answered publicly.

The Kremlin, for its part, has denied any specific knowledge about the detentions. On April 27, presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov, however, speculated that perhaps individuals with fake press IDs had prompted the police to detain reporters covering the Navalny rally.

“This is a completely egregious act,” Peskov said of the alleged media masquerades.

He may have been referring to the April 21 detention of Ivan Kabakov, the coordinator of Navalny’s St. Petersburg office, who, according to RIA Novosti, presented his former Dozhd ID to police, Mediazona reported.

One rights activist, though, believes the “egregious act” lies with the government.

Calling the detentions of both journalists and activists following the pro-Navalny rallies “a new and extremely disturbing turn of events,” Amnesty International Russia Director Natalia Zvyagina urged Russia on April 27 to ban the use of facial-recognition cameras at protests.

As yet, there has been no response.