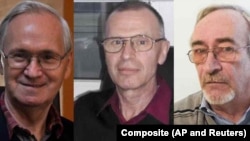

Three Russian scientists who participated in the Soviet-era production of the nerve agent Novichok now dominate Russia’s coverage of the poisoning of influential Russian opposition leader Aleksei Navalny. Vil Mirzayanov, Leonid Rink, and Vladimir Uglyov are the only such scientists to speak out on this topic to Russian media. But they are a divided group, and their personal differences extend to how they interpret Novichok’s link to that poisoning.

Out of the three, Leonid Rink, a former laboratory director at the State Institute of Organic Synthesis Technology (GITOS) that developed the nerve agent in the late Soviet era, has become a regular on Russia’s state-run TV channels and news websites. These outlets look to Rink, whom they present as a “creator” of the Novichok (Newcomer) group of nerve agents, to explain why the poison, as the Kremlin maintains, could not have been used against Navalny.

Initially, the chemist comments as a scientist; then, as a political analyst.

If Navalny had been poisoned by Novichok when he fell ill during an August 22 flight from Siberia to Moscow, “[t]here would be convulsions and so on. Completely different symptoms,” Rink told Sputnik earlier this month.

And the doctors who initially treated Navalny in the Siberian city of Omsk would have detected its presence right away, he assured Rossia-24 on September 23.

No such traces were found, he earlier speculated to the channel, because Navalny “and his supporters staged this performance” to help the 44-year-old activist “make ends meet.”

Navalny, colleague Lyubov Sobol, and Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation face an 88-million-ruble ($1.2 million) fine for defaming Moskovsky Shkolnik (Moscow Schoolboy) Company, a catering service that the group alleged had spread dysentery throughout Moscow’s school system.

The fine led to Navalny announcing the closure of the Anti-Corruption Foundation in July. On September 24, the activist’s Moscow apartment was seized in connection with this claim, his spokeswoman, Kira Yarmysh, tweeted.

Moskovsky Shkolnik’s purported owner, Kremlin-linked businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin, purchased the debt from the company after Navalny was poisoned.

Rink did not elaborate about how “staging” a Novichok poisoning – a theory also reportedly floated by Russian President Vladimir Putin -- would assist in this matter.

But the scientist maintains that he is speaking out on Novichok simply to set the record straight.

“When our Zakharova (Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova) gave a speech and said that there was and is no Novichok here (in Russia), this was simply untrue,” he underlined to Current Time. “And dozens of people from Russia, who got away … with evidence, easily disproved her. For that reason, I spoke up.”

Similarly, in 2018 he also denied that Novichok had been used in the United Kingdom on ex-military-intelligence-officer-turned-double-agent Sergei Skripal. In an interview with the state news agency RIA Novosti, he cited а lack of motive by the Russian government and the fact that Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, did not die immediately.

Yet Rink’s former colleagues at GITOS have their own explanations for why, like the Kremlin, he consistently refutes any reports about the use of this nerve agent.

“Because he has his snout in feathers,” said Vladimir Uglyov, using an expression that indicates participation in an unseemly activity. “And now, he’s earning his own silver coins.”

Apart from his television appearances, Rink works as an expert for the State Duma’s Defense Committee, а member of scientific academies, and the owner of a medical-products company.

Uglyov, who developed Novichok compounds over 15 years, disputed that Rink had ever worked as a Novichok developer, though. “He got plugged in at the end of the entire program,” he said.

The Novichok program began in the 1970s at the State Institute of Organic Synthesis Technology in the closed Russian town of Shikhany. Officially, it had ended by the time Russia signed an international agreement banning the manufacture of chemical weapons in 1993.

In an interview with The Bell, Rink stated that he came to GITOS in 1987 to run a reorganized biochemical laboratory that developed “secret systems,” and worked in this field until 1991 until a ban was imposed. He then switched the lab over to performing chemical syntheses for medicine, he said.

Uglyov considers this time period critical for understanding the position Rink now takes on Novichok and Navalny.

The chemist has acknowledged selling about а gram of GITOS’ Novichok in 1994 for around $1,500 to $1,800 – at the time, a hefty sum of money amidst Russia’s post-Soviet economic crisis.

In a deposition to investigators, Rink said that he had divided the poison into several quarter-gram vials and placed them in his garage.

The buyers eventually passed the nerve agent on to individuals linked to the 1995 poisoning of Rosbiznesbank Chairman Ivan Kivelidi. Both Kivelidi and his secretary, Zara Ismailova, died from contact with the poison, which had been applied to the handle of the banker’s office phone.

A Justice Ministry specialist who performed an autopsy on Kiveldi’s body died as well.

Though he acknowledged to investigators that he understood that the buyers “intend to use the agent against people,” Rink has never been held accountable.

In 2007, Rosbiznesbank’s deputy chairman, Vladimir Khutsishvili, was sentenced to nine years in prison for the deaths. Rink, who served as a chief witness for the prosecution, received only a year on probation.

His former colleagues believe that this is why Rink now adopts the Kremlin’s line on the Navalny poisoning.

“Rink, well, he’s playing. But he’s not a stupid guy,” commented former GITOS chemist Vil Mirzayanov, who revealed Novichok’s existence in 1992. “I know him. Or to be more exact, knew him.”

“But he doesn’t do this by his own free will,” he claimed.

Unlike Rink, Mirzayanov and Uglyov both supported claims that Novichok was used to poison the Skripals. They also believe German, French, and Swedish laboratories’ reports that traces of the poison were found in Navalny’s body.

Now released from a Berlin hospital after more than a month of treatment, the anti-corruption activist, who remains in the German capital, posted on Instagram on September 23 that he plans to have “physical therapy every day.” He mentioned difficulty with his balance, controlling his fingers and writing, and throwing a ball.

Navalny was evacuated to Berlin’s Charite-Universitatsmedizin hospital on August 22 after spending roughly two days at a hospital in the Siberian city of Omsk, where his Moscow-bound flight had made an emergency landing on August 20 after he passed out on board.

Mirzayanov, who formerly ran GITOS’ technical counter-intelligence department, has apologized to the opposition leader for his own role in producing the poison that could have cost him his life.

He takes that message to all media, including those who call him a traitor and defector.

“I try to answer everyone, regardless of whether or not they always put me in an attractive light,” the chemist said. “This doesn’t bother me. I’ve already gotten used to taking the blow."

“For 30 years, I fought against Novichok. I won’t praise myself, but, if not for me, the world still wouldn't know about Novichok.”

But Leonid Rink and Vladimir Uglyov have their own views on that contribution.

In 1994, prosecutors charged Mirzayanov with divulging a state secret after scientist Lev Fedorov and he released information in 1992 to Russian and U.S. media about Russia’s ongoing chemical weapons capabilities.

After prosecutors dropped the secrecy case for a lack of evidence, Mirzayanov emigrated to the U.S. in the mid-1990s. In 2008, he published the formula for Novichok in his book State Secrets: An Insider’s Chronicle of the Russian Chemical Weapons Program Secrets.

For Rink, who has described Mirzayanov as “a talented chromatographer” (a person who separates the parts of a chemical mixture), this still rankles.

He attributes the book’s publication to financial motives. He has called for the scientist to apologize to “the Soviet bureaucracy” and Russia’s Federal Security Service for divulging a state secret, and to the world at large for releasing the Novichok formula.

“For that reason, we’ve gone our separate ways,” Rink commented to Current Time. “Because he’s an ordinary traitor. What attitude can I have toward him?”

Uglyov does not go that far, but does charge that Mirzayanov’s published Novichok formula contains mistakes. He rejected his apology to Navalny because, as a chromatographer, Mirzayanov has no direct experience developing Novichok, he told RBC.

In a 2018 interview, Mirzayanov told Current Time that guilt and a desire to encourage the Organization for the Prevention of Chemical Weapons to take action against “a weapon of mass destruction of people” had prompted his disclosures.

“A scientist, when working on creating such weapons, must ask the question: ‘What is this for? Who is it for?’” he commented.

As the Navalny-Novichok debate rages on, little suggests that Russia has yet resolved those questions.