President Alyaksandr Lukashenka is not the only familiar political figure in Belarus’ August 9 presidential vote. Overseeing the election process is a 67-year-old woman who has organized all of the Eastern European country's presidential elections and referendums since 1996: Central Election Commission Chairwoman Lidiya Yermoshina.

“She owes everything to Lukashenka, and he owes everything to her,” commented one Belarusian political analyst. Current Time explored how an obscure, regional bureaucrat became the leader of Belarus’ Central Election Commission, and what her nearly 24-year track record could mean for the conduct of the country’s 2020 presidential election and beyond.

The Nomenklatura’s ‘Cinderella’

Yermoshina, a lawyer from the large eastern Belarusian city of Babruysk, does not dissimulate about what attracted her to the Central Election Commission: It was neither a passion for politics, nor experience with elections.

In November 1996, Yermoshina, then head of the Babryusk city government’s legal office, was dispatched to a Central Election Commission conference in Minsk, the Belarusian capital, as the representative of the Mohylev regional election commission. For the 43-year-old single mother who lived with her mother, these CEC meetings gave her access to a different world.

“They opened up an opportunity to escape from the routine in the Babruysk city executive committee, to go to theaters in the capital, have some kind of social life, if I can put it that way,” Yermoshina reminisced to the Naviny.by outlet in 2016.

The timing of her 1996 trip would prove critical.

President Lukashenka, then in his first term of office, was frantically looking for a replacement to run the CEC ahead of a planned national referendum on expanding his powers. Finding a team player loyal to the president was what mattered most.

Lukashenka’s colleagues knew Yermoshina and recommended her to him. The 42-year-old president had an extensive background in her native Mohylev region.

He had spent his childhood there and graduated from the Mohylev State Pedagogical University. He had worked in the region as a Komsomol (Young Communist League) secretary and Communist Party instructor, later becoming a construction factory deputy director, collective farm manager, and member of Mohylev’s Communist Party leadership. He then had represented Mohylev in Belarus’ parliament, the Supreme Soviet.

The job of CEC chairwoman became Yermoshina’s.

It was a rapid transformation. Yermoshina arrived in Minsk on the morning of November 14, 1996 and was named by the president – in violation of Belarus’ then constitution, critics say -- as the acting head of the CEC. “In the evening, I returned to Babruysk for my toothbrush, and the next day left for Minsk to preside over the elections,” she recounted to Argumenty i Fakty (Arguments and Facts).

Considering herself unequipped for such a senior post, Yermoshina at first thought that she would try it out for two weeks. “I was even afraid to say a word in front of a TV camera,” she remembered.

But Yermoshina could not decline such an offer, believes Belarusian political strategist Alyaksandr Feduta, a former Lukashenka spokesman and campaign aide, who described the CEC chairwoman as “intelligent, cynical – in her way, super sharp.”

“She was a single mother sitting in Babruysk without any perspectives, and, here, they propose to her that she join the national elite,” Feduta said. “Naturally, she used this chance and faithfully serves Lukashenka, to whom she owes everything, and he now owes her everything, too.”

Yermoshina calls herself “a provincial” who became the “Cinderella” of Belarus’ “nomenklatura.”

“Such careers are made during major political and social upheavals, when there’s no time to select candidates,” she commented to Argumenty i Fakty. 1996 would prove such a year for Belarus.

The 'Time Of Upheaval': Belarus’ 1996 Referendum

That fall, when Lidiya Yermoshina first appeared on Belarus’ political scene, President Lukashenka was fighting with parliament, then called the Supreme Soviet. In August of 1996, Lukashenka had sent to parliament a request to hold a national constitutional referendum. The central question would be about extending his powers.

The proposed amendments to the constitution would give the president the right to dismiss parliament, appoint Constitutional Court judges and ministers, and issue decrees that have the force of law. As of 1996, his term would shift from five years to seven.

Belarus would become, in essence, a presidential republic, headed by a president who would no longer be able to be removed from office for violating the constitution.

Arguments About The Referendum

Aside from the president’s powers, the 1996 referendum contained other controversial questions for voters to decide:-changing the date of Belarus’ Independence Day from July 27 (the date in 1990 when the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic had declared its sovereignty) to July 3 (the date in 1944 when Soviet troops liberated Minsk from Nazi Germany);-authorizing private land sales and purchases;

-abolishing the death penalty; -holding direct local elections;

-including all state expenses within the national budget

The Supreme Soviet agreed to the referendum, but also proposed its own changes to the constitution, including making Belarus a parliamentary republic.

On November 4, 1996, the Constitutional Court announced that the law does not foresee using a referendum to make changes to those parts of the constitution that Lukashenka had proposed. The results, it said, could only be seen as advice. In response, President Lukashenka stated that the Court was limiting the rights of citizens to participate in a referendum. He immediately issued an order that made the referendum’s results obligatory and “not requiring confirmation.”

At the time, Viktar Hanchar, a lawyer who had actively collaborated with Lukashenka during his 1994 presidential campaign, headed the CEC.

Unable to build a rapport with President Lukashenka, he had resigned as deputy prime minister after several months. He was now part of the opposition, and had been named by parliament to head the CEC – an unimaginable scenario later in the Lukashenka era.On November 14, 1996, the same day that Yermoshina arrived in Minsk, Hanchar announced at both a press conference and on Russian television that he would not confirm the final results for the November 24 referendum if multiple violations of the election code occurred.

That same day, Lukashenka issued a decree that removed Hanchar as chairman of the Central Election Commission.

Viktar Hanchar's Fate: An Unsolved Mystery

The Central Election Commission later released a statement, signed by the new chairwoman, Lidiya Yermoshina, that alleged that Viktar Hanchar had discredited the CEC with his categorically political statements. As a result, the statement claimed, it was not possible to retain him as head of the CEC.

Much later, after Lukashenka had conducted the 1996 referendum, the president dismissed the Supreme Soviet and formed a two-chamber National Assembly. Hanchar was among those who began to prepare for an “alternative” presidential election in 1999. Hanchar headed an “alternative” CEC for this de facto vote and set up a network of non-official election commissions.

However, in September 1999, he and his friend, businessman Anatol Krasovski, disappeared in mysterious circumstances. The criminal investigation, insisted upon by Hanchar’s relatives, reached no conclusions. It was put on hold since a suspect had not been identified. In 2019, a former member of the Belarusian Interior Ministry’s Special Rapid Response Unit, alleged to Deutsche Welle that the creator of this unit, Colonel Dzmitry Pavichenko, had shot dead both Hanchar and Krasovski in Belarus’ Vitebsk Oblast. Yury Garavski claimed that Hanchar had “compromising material” on Lukashenka and those at the top of the Belarusian government had wanted to get rid of him. Pavichenko has denied this allegation.

Lukashenka’s switch of officials had directly violated the constitution. At the time, only the Supreme Soviet had the powers to fire and appoint heads of the Central Election Commission; the president did not.

Nonetheless, on November 15, 1996, riot police forcibly blocked Hanchar, who had not yet received the presidential decree, from entering his CEC office. An enraged Supreme Soviet Speaker Semen Sharetski argued that it had been done “for seizing power!”

That day, Hachar called Yermoshina and underlined that he did not recognize her appointment. The conversation led to nothing: “Mrs. Ermoshina, it seems, is still in a state of euphoria [from the presidential decree naming her head of the CEC],” he remarked drily.

Constitutional Court Chairman Valer Tikhinya advised the president to cancel his decree in order to uphold “constitutional legality.” But Lukashenka did not respond. After the referendum, Tikhinya, refusing to be sworn into office on the new constitution, would resign.As for Belarus’ new Central Election Commission boss, she later took a detached view on the events of 1996.

“In politics, it can happen that you have to do things that are subject to criticism, but criticism on formal grounds. Precisely formal grounds,” she commented to Naviny.by in 2016. “In fact, the head of state had the grounds to consider the head of the CEC a politically motivated individual, who was in conflict with those tasks that are entrusted to the CEC.”

How Parliament Tried To Impeach Lukashenka

The Constitutional Court on November 19 began work on a case to impeach the president. Seventy-three out of 198 parliamentarians signed on. A hearing was scheduled for November 22, 1996.

But on the evening of November 21, Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, Federation Council Speaker Yegor Stroyev, and State Duma Speaker Gennady Seleznev arrived in Minsk, at the invitation of President Lukashenka. They had been summoned to help regulate the conflict.

On the morning of November 22, the parties signed an agreement that the Supreme Soviet would stop its impeachment case and that the 1996 referendum results would be considered final. But even before this agreement, 12 Supreme Soviet deputies reportedly had rethought their positions and withdrawn their support for impeachment. (They later alleged that the Lukashenka administration had pressured both them and their relatives.)

On November 23, President Lukashenka declared that the referendum’s results would be final since the Supreme Soviet had not been able to execute its promises.

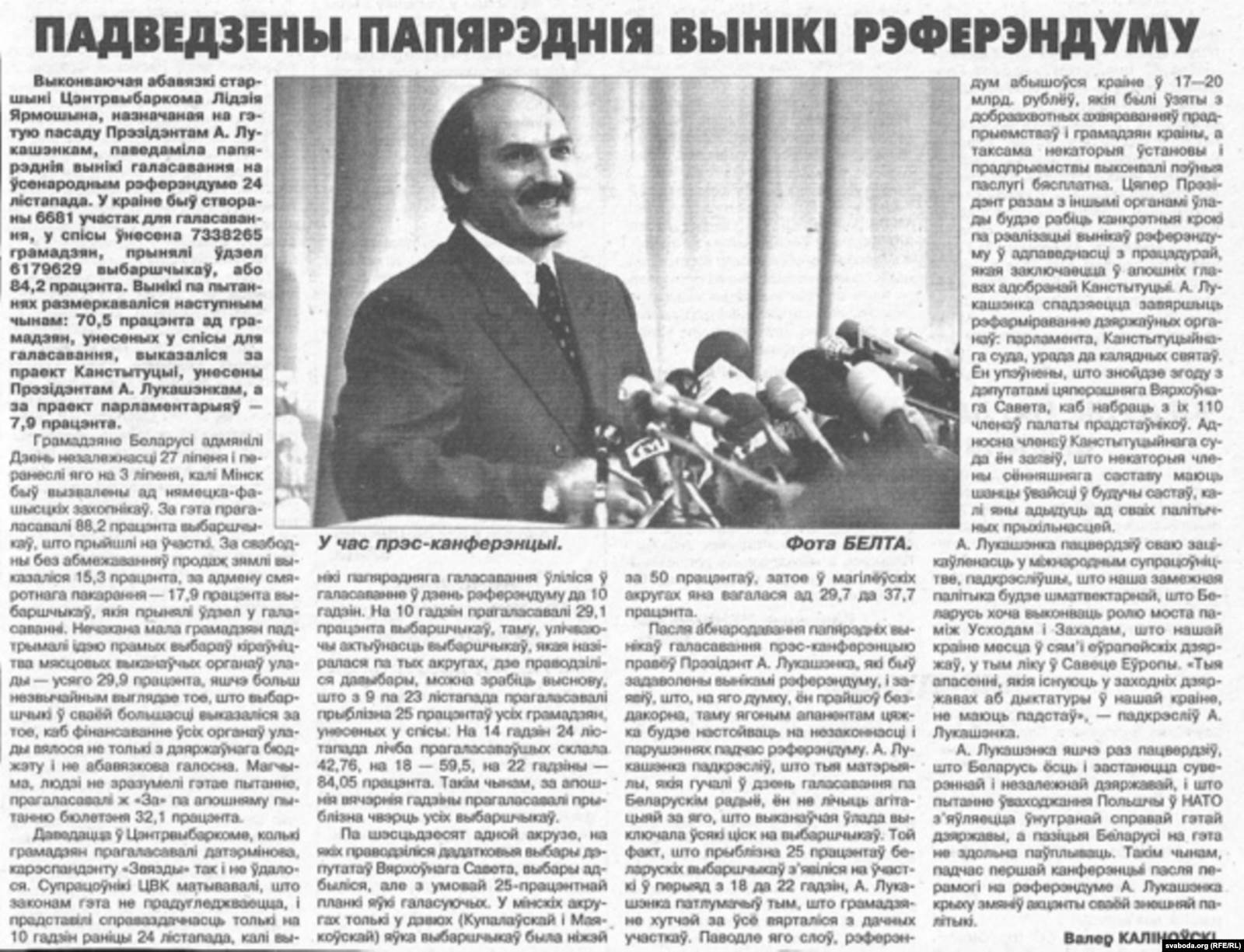

On November 24, 1996, the referendum took place. Early voting for the referendum had begun 12 days before the final text of the proposed amendments was available.

In some regions, 50 percent of the total vote cast had occurred during this 12-day period.

Hanchar flagged this anomaly, and also noted others: 20 percent of the vote was cast between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m., a time frame that usually accounted for 7 to 9 percent of the vote, he said.

But Yermoshina proceeded with the results: “On practically all questions, the president received citizens’ staggering support,” she announced.

Based on official figures, 83.73 percent of voters had approved Lukashenka’s constitutional amendments.

Based on official figures, 83.73 percent of voters had approved Lukashenka’s rewritten constitution. The clock on his presidential terms was set back to zero. Lukashenka received an additional two years in office.

And on December 6, 1996, Lidiya Yermoshina became the full-fledged chairwoman of Belarus’ Central Election Commission.

‘From The President’s Team’

If Yermoshina’s promotion from the provinces took many Belarusians aback, her longevity at the Central Election Commission proved no surprise. Above all, Lukashenka values her “complete obedience,” stressed Garry Pogonyaylo, chairman of the Belarusian Helsinki Committee’s legal commission.

Yermoshina, who has her suits made by an atelier run by the Presidential Property Management Administration, calls herself “a person from the president’s team.”

“And how could it be otherwise?” she asked Euroradio in 2011. “If the principle is placed in the constitution that the leader of the state appoints the chairperson of the CEC, then it follows that he himself or his service selects this person. And the country’s leader should trust this person. In this sense, I’m from the president’s team."

“But I can tell you that the Central Election Commission has never sensed any pressure at all on its activities from some state organ,” Yermoshina continued. “Including, from the leader of the state.”

In 2004, via another referendum, that leader gained the option to serve altogether without a term limit.

Article 112 of Belarus’ Election Code forbids putting to a referendum questions related to the election or dismissal of a president, but that gave the CEC head no pause.

As in 1996, the CEC-organized referendum delivered the president a solid success.

Less than a month before this referendum, a tracking poll by The Gallup Organization/Baltic Surveys had shown that only 39 percent of 3,000 Belarusian respondents had favored lifting the two-term limit. But based on official data for the vote, 79.42 percent of Belarusian voters allegedly agreed to abolishing the constitutional restrictions on Lukashenka’s time in office.

That approximate percentage would become a constant for his official results in all national votes to come.

In March 2006, he again was reelected as president, with 82.6 percent of the vote, according to the official results. Six percent of the vote or less went to the remaining three candidates.

As in 2020, the government alleged that it had proof that the government’s opponents planned violence to disrupt the elections.

Several days before the elections, the Interior Ministry and KGB announced that they had detained people who were preparing a terrorist attack. These individuals allegedly intended to poison Minsk’s plumbing system with water contaminated by dead rats. A video with one such confession was shown. What happened to these detainees and how the investigation ended remains unknown.Widespread detentions and arrests also marked the election. Activists from the independent election monitoring group Partnyorstva (Partnership) were sentenced to prison for carrying out activities for “an unregistered organization.”

Violence also occurred. During the election campaign, riot police assailed and detained presidential candidate Alyaksandr Kozulin.

Overall, the CEC received 231 complaints about campaign and election irregularities, which Yermoshina herself mostly answered. She later told journalists, though, that the body had “no information about falsifications.”The CEC never reviewed the complaints at an official session of its members.

Following the vote, around 30,000 people came out to protest in downtown Minsk. Four days into the demonstration, riot police brutally cracked down on participants. Government prosecutors stated that more than 500 people had been detained or arrested; dozens were wounded.

“Law enforcement worked wonderfully, and nature, snow, and the absence of ideas and strong leaders broke up the demonstration’s participants,” Yermoshina commented at the time, TUT.by reported.

The European Union, Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and the United States condemned the Belarusian authorities’ actions as not in keeping with a democratic election. The parliaments of Belarus’ western neighbors, Poland, Lativa, and Lithuania, also took issue with the conduct of the vote, as did nearby Estonia.

The Lithuanian Foreign Ministry stated that the election had occurred “in an intimidating environment, without efforts to ensure freedom of the press and equal conditions for all candidates,” The Baltic Times reported.

The European Union and United States placed Yermoshina and Lukashenka both on travel bans for the vote. The CEC chairwoman denounced what she termed the EU’s bias, but regretted that the Belarusian CEC could no longer participate in conferences in the EU.

President Lukashenka later announced that the 2006 elections had been falsified, but not in the way the international community had believed. In reality, he claimed, 93.5 percent of Belarusian voters, not 82.6 percent, had voted for him.

“Europe told us that this is not a European percent: ‘Look, you do a European percent, and we’ll recognize your elections [as valid],’” he alleged EU representatives had said. “But if they now recount all the ballots … I don’t know at all what to do with these ballots,” he told Ukrainian journalists in November 2006.

More than once, the head of the CEC has had to remark that Lukashenka was joking when addressing election topics.

This time was no different: Polling stations in hospitals and military bases had initially projected that “more than 90 percent” of their vote had gone to Lukashenka, Yermoshina told Naviny.by. “As a joke, it was discussed that this percent is not ‘European,’” she elaborated. The final 2006 election results, however, were based completely on the voting protocols, she underlined.

Showing ‘Loyalty’ In The 2010 Election

By 2010, the date of Belarus’ next presidential election, Yermoshina had nearly a 14-year track record of unwavering support for President Lukashenka. But in her view, that should only be expected from the country’s top election official. “Loyalty to the government is a prerequisite for the work and existence of each official in office,” she commented to the news site Naviny.by in 2016. “This is necessary. If you want to be disloyal, free, get out of the state system. So long as you’re in it, you should be loyal. This is a condition for the existence of any state.”

Yermoshina’s opinion about loyalty extends not only to officials, but also to state-funded journalists. Belarusian TV viewers learned this in 2010.

During an election-day broadcast of the state-run ONT TV channel’s Vybor (Choice) talk show, host Syarhey Dorofeyev asked Yermoshina about reported violations during early voting. He also asked why students were compelled to vote early; why observers are not allowed to monitor the polling stations during the night; nor protesters to gather in a Minsk square to contest the results and call for repeat elections.

After several questions by the host and journalists from non-state outlets in the audience, Yermoshina excused herself. Turbulent protests already had begun in Minsk’s Lenin Square, not far from the CEC building.

CEC employees, “fragile women,” were working compiling vote counts, she said, “and I am sitting here and discussing beautiful topics. I can't be here anymore. "

State-run media would later allege that the opposition attempted to storm the Belarusian government headquarters; activists counter-charged that the building’s damage was the work of the security services attempting a provocation.

Yermoshina later implied that turmoil had prompted her sudden departure from the talk show; not because host Dorofeyev’s questions had made her angry.

“The CEC employees are those very same children, people, who trusted you,” she commented in 2011 to the magazine Sextus. “Can a mother, knowing that her children are in trouble, really calmly stay somewhere? This is absolutely feminine, maternal behavior.”

Responding to Vybor host Dorofeyev’s questioning of the CEC chairwoman, President Lukashenka himself called him “a young journalist who needs to be put in his place.”

The host was subsequently taken off the air, and eventually fired for supposedly not meeting ONT’s standards. Yermoshina expressed no regrets.

“Don’t forget, ONT is a state channel, and if you get a salary on a pro-government channel, you should follow a line close to the official line” on policy, she advised Euroradio in 2011. “Even though you also have your own personal and journalistic view on events.”

The Vybor talk show never again returned to the air.

Women Should ‘Sit At Home, Cook Borscht’

“Fragile women” became a recurring theme in Yermoshina’s remarks.

The morning after the 2010 presidential elections and the Vybor broadcast, Yeremoshina stressed that the riot police who violently broke up the protest had defended “our fatherland,” “law and order,” and “innocent people, fragile, size-42 (size 6) women.”

When journalists at a press conference objected that “fragile women” had also been among the protesters beaten by police, Yermoshina retorted that "using a stick against violators [of the law], regardless of gender," is a requirement of law enforcement.

The protests, she said, had nothing to do with “the election procedure.”

Her next remarks could have implications for the 2020 vote, in which one female candidate, Syvatlana Tsikhanouskaya, and two female associates, Veranika Tsapala and Maryya Kalesnikova, routinely stage demonstrations that condemn the authorities.

In 2010, Yermoshina fumed that the women protesting against the presidential election results “have nothing to do!” If they did, she continued, “[t]hey would sit at home, cook borscht, and not run around in squares. This doesn’t even enter my head.”

A woman participating in such events is shameful, and has something “wrong with her intellect,” she summarized.

Cooking borscht, baking a cake, or reading books to their children became Yermoshina’s recommendations for female protesters. “How long have these ladies who wandered around this square [in 2010] read books to their children?” she asked Euroradio in 2011.

These remarks prompted the Russian feminist group Pro Feminism to name Yermoshina its Sexist of the Year for 2010.

But some mothers of imprisoned activists, considered political prisoners, responded that Yermoshina had denigrated all of Belarus’ mothers with her words.

“The women who went out to the square think about the future,” said Yelena Likhovid, whose 21-year-old son, Nikita, had been condemned to three and a half years in maximum-security prison colony for taking part in the December 19, 2010 protest. “They want their children to live in a free country.”

Not A 'Career, But A Destiny'

In 2015, Lidiya Yermoshina was removed from the EU sanctions list: Five presidential elections, in which Alyaksandr Lukashenka had been victorious, had taken place without major political upheavals. Yermoshina took a vacation in Italy with her son, Aleksey Yermoshin, also a lawyer. She told journalists that it was a modest vacation; they had spent around 2,000 euros ($2,364) – an amount nearly equal to an average Belarusian household’s entire annual income for 2015, according to the CEIC database.

Two years later, at the age of 40, Aleksey Yermoshin, the son she had declared to be the central person in her life, died. In his place, commented Feduta, Lukashenka likely has obtained even more importance for the twice-divorced woman.

Yermoshina had said she expected to leave her post as chairwoman of the Central Election Commission in 2016, when her contract expired, but indicated that Lukashenka had not yet found a “suitable substitute.”

The 2020 election, however, could be her last. Yermoshina, who lives in the Minsk suburb of Drozdy favored by senior officials, already is a few years over the Belarus’ civil service’s age limit of 65. In 2021, the entire Central Election Commission’s term expires, and a new body must be chosen.

Even if Yermoshina leaves, commented human-rights lawyer Pogonyaylo, little will change at the CEC. Its members “would never dare to argue with anyone,” and “always take a decision that is correct for the authorities,” he said.

“[Y]ou simply can’t count or hope that someone will suddenly there start to express a dissenting opinion.”

Who would or could take Yermoshina’s place is not known. But this election official will look only to the president to decide whether she stays or goes.

“This is no career, but a destiny,” she commented in 2011. “And when the country’s leader says that you must work, that’s not open for discussion.”

-This This article is an edited translation by Elizabeth Owen of Командировка в Минск на 24 года. Рассказываем о Лидии Ермошиной – бессменной главе ЦИК Беларуси, при которой всегда побеждал Лукашенко by Alena Shalayeva.

Find out more:

Belarus’ Early Voting Brings Early Complaints About Presidential Election’s Conduct

With three days to go before the start of regular voting in Belarus’ presidential election, Belarusian police have detained independent election observers amidst reports of unusually high official turnout for early voting, while supporters of lead opposition candidate Svyatlana Tsikhanouskaya...

With No Day In International Court, Judicial Options Slim For Belarusian Detainees

Hundreds of individuals have been arrested or fined by police during Belarus’ presidential election campaign in recent weeks, but, unlike in other formerly communist-run European countries, Belarusians who believe they have been wronged have no recourse to international courts. The reason is...