Mighty Memories: Memorial's Fight To Remember Stalin's Victims In The Urals Labeled as 'foreign agents,' Memorial activists in Yekaterinburg, Russia still refuse to forget the past

As the 30th anniversary of the collapse of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991 draws closer, Russia’s Memorial movement, a network of advocates against the Stalin-era repressions that cost millions their lives, is itself facing a potential end. Citing alleged violations of Russia’s “foreign agent” law, Russian prosecutors have requested that courts close both International Memorial, a non-profit group that acts as an umbrella for members of the Memorial movement, and the Memorial Human Rights Center, which oversees its human rights work. The Supreme Court and Moscow City Court have postponed hearings for these suits until mid-December 2021.

To clarify the debate over Memorial’s work, Current Time examined its role in one regional Russian city of over 1.5 million – Yekaterinburg, the largest city in the Urals, once the heartland of Soviet manufacturing. Here, Memorial members, like their counterparts in Moscow, also began working in the late 1980s to uncover and make known the atrocities of the Stalin era.

Like Memorial’s other communities, the Yekaterinburg Memorial Society is registered as a separate organization from the two Moscow-based Memorial groups, both officially deemed "foreign agents." It, too, however, carries the "foreign agent" label.

The government charges that the two Moscow-based groups have repeatedly violated Russia’s “foreign agent” law on entities that receive foreign donations and conduct “political activities.” It claims that the pair have failed to label their materials as from a “foreign agent” and have justified terrorism and extremism. Prosecutors assert that Memorial’s list of alleged political prisoners supports this last allegation.

Memorial sees these arguments as purely political. It objects that it already has paid around 6.5 million rubles (over $87,926) in fines for supposed violations of the “foreign agent” law, and that such violations are not sufficient grounds to “liquidate” an organization.

The President Boris Yeltsin Center, numerous historians and other scholars, lawyers, artists, writers, and cultural figures have expressed the hope that Memorial will continue its work.

In Yekaterinburg, nearly 1,800 kilometers (1,118 miles) to the east of Moscow, Memorial activists are closely watching the government's attempt to shutter International Memorial and the Memorial Human Rights Center.

Prosecutors’ cases also have potential ramifications for what the Yekaterinburg Memorial group itself can do to remember the victims of political repressions, believes the non-profit’s chairman, Aleksei Mosin.

Rehabilitating Victims, Searching For Remains

The non-governmental group Memorial appeared in Moscow in 1987, with the birth of glasnost. Gradually, Soviet citizens began to demand a discussion of repressions under Soviet leader Josef Stalin, to talk about political prisoners and dissidents. Later, these demands would lead to an examination of the Soviet Union’s 1940 Katyn, Poland massacres, too.

In Sverdlovsk, the Urals region’s main city, now known as Yekaterinburg, Memorial took shape as well. What had earlier been said in half-whispers in the kitchen now was being discussed openly at large-scale, public meetings, including in the city’s Museum of Youth, its then director, Vladimir Bykodorov, recollects.

“In those days, the state encouraged the restoration of the fates of the repressed,” recounted Bykodorov, now deputy director of the Sverdlovsk region’s Local History Museum. “Concrete cases were discussed at meetings, the children of the repressed gave speeches, shared their memories and information. As a result, an enormous amount of work to rehabilitate the repressed was done by Memorial, in close contact with the authorities.”

Gradually, more and more Sverdlovsk residents began to find out about the meetings in the Museum of Youth. With time, Memorial’s role became even more central in those discussions.

In 1989, an elderly man, Ivan Dulya, who had worked on the construction of the city’s Dinamo sports center, attended one of these meetings.

In 1967, while building the Dinamo sports field, Dulya had come across human remains. Looking at the skulls, the builder saw bullet holes in them. Dulya told his managers about his find, local historian Vadim Viner, a Yekaterinburg Memorial Society member, remembers him saying.

Dulya’s information reached law-enforcement organs, but they reportedly recommended that he forget everything that he saw.

As a result, for more than 20 years, Ivan Dulya had been unable to speak publicly about these remains. But Dulya’s tale was not the only one.

Two more people came to Memorial’s meetings and said that they had guarded mass burial sites at the Moscow Highway’s 12th kilometer mark. Apple trees were later planted in this plot of land.

Not only Memorial learned about these sites, but the entire city. Mass media began to cover the topic.

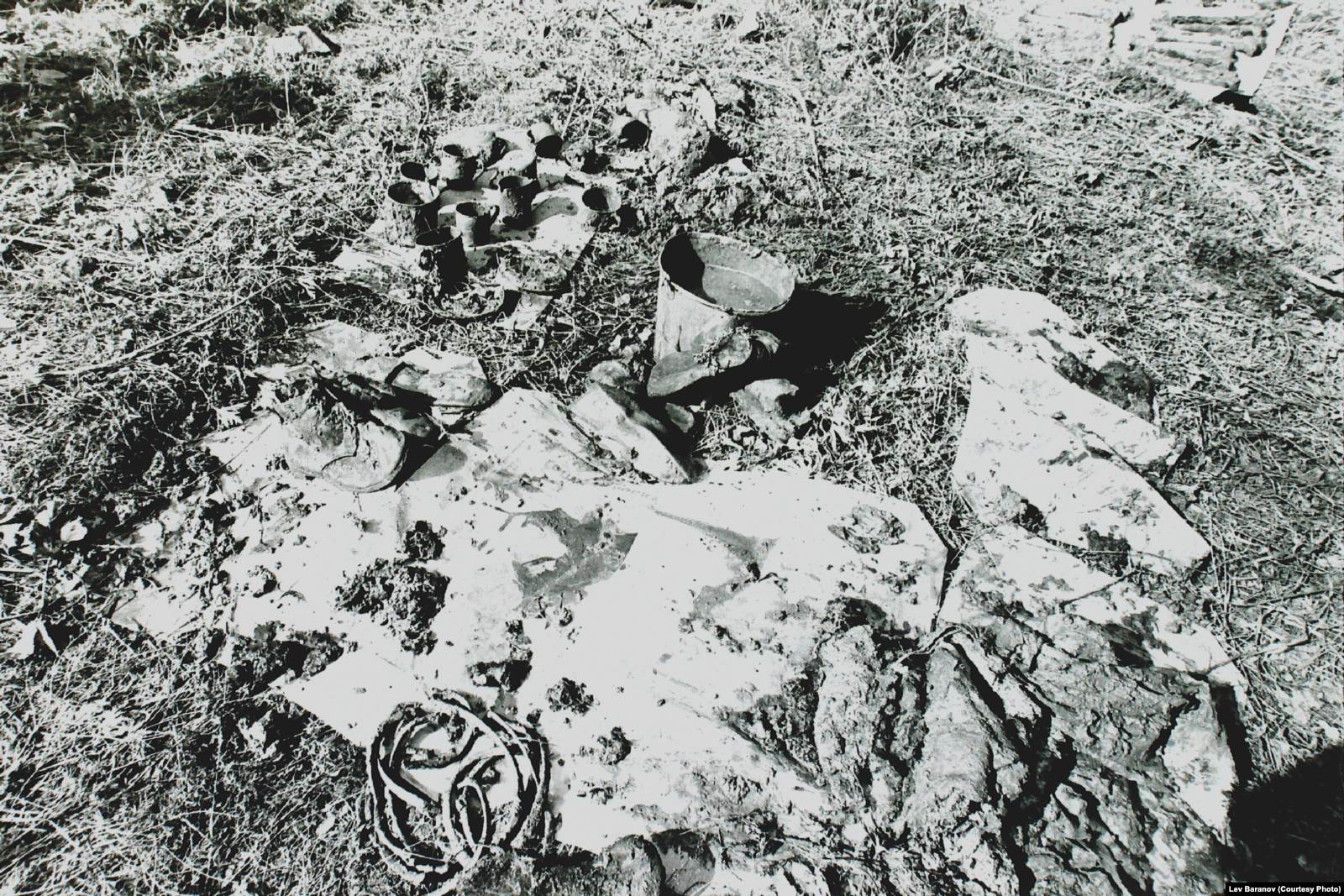

In 1991, the Sverdlovsk regional prosecutor’s office excavated one cubic meter of earth from the 12th kilometer mark. The remains of 31 people were discovered in this sample.

During the site investigation, documents were found in the name of Filip Zagursky, a native of western Ukraine who was executed in 1938. The investigators and prosecutor’s office concluded that some of the people found at the 12th kilometer mark had been executed in the basements of the city’s NKVD, or secret police, building at 17 Lenin Street in downtown Yekaterinburg.

The NKVD then took the bodies in trucks along the Moscow Highway and threw them into a pit.

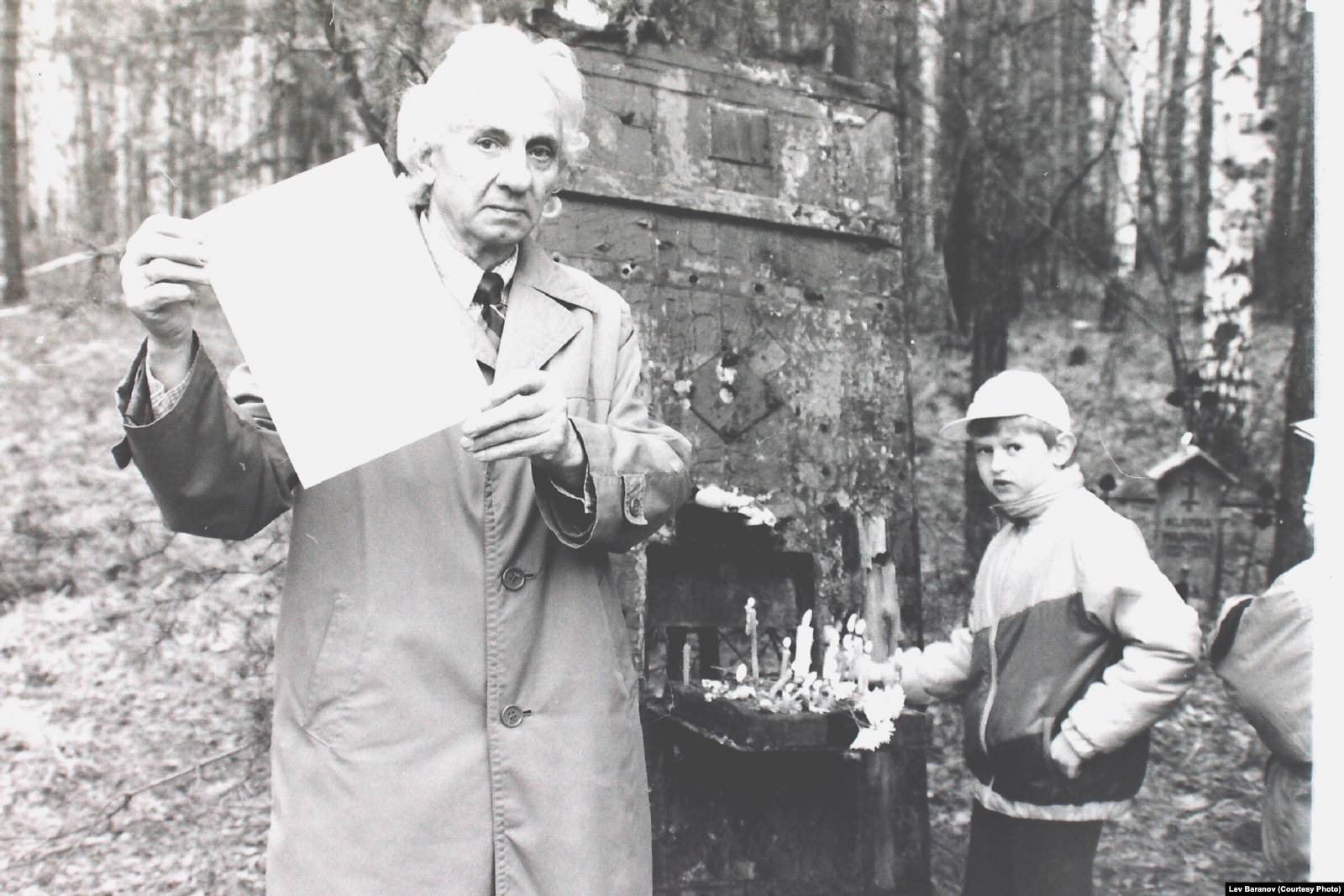

As they learned about the site of these mass burials, hundreds of people over several months went to the 12th kilometer mark on the Moscow Highway. With time, thanks to these visits, a grassroots memorial took shape there. One person would come with flowers, someone else with candles and photographs of loved ones who had been victims.

Another local resident, strolling through the forest, saw something resembling a trunk in the ground. It proved to be the corner of a prison door. The man dug it up and brought it to the grassroots memorial.

A Permanent Memorial For Stalin’s Victims

In 1992, the newly formed Yekaterinburg Memorial Society requested the city’s mayor, Arkady Chernetsky, to rebury the remains of victims found at the 12th kilometer mark and to designate some 100 hectares (247 acres) at the site as an official memorial area.

At the time, the Yekaterinburg Memorial chairwoman, Anna Pastukhova, a former Russian language and literature teacher in a technical college, actively cooperated with local officials to define the borders for this area.

In the autumn of 1996, an official memorial to the victims of political repressions opened at the Moscow Highway’s 12th kilometer mark, but it amounted to only 1.6 hectares, or about 4 acres; less than 2 percent of the proposed burial grounds.

To date, though, the names of 18,475 people, executed in Sverdlovsk between 1937 and 1938, have been engraved on memorial plaques at the site, according to the Yekaterinburg History Museum.

The official boundaries for the site’s burial grounds, however, still have not been defined, said Yekaterinburg Memorial Society activist Anatoly Svechnikov.

Meanwhile, more mass burial sites have been found.

In October 2020, archaeologists found two new sites at the 12th kilometer mark that could contain between 20,000 to 40,000 people, the Russian daily Kommersant reported.

One of the sites, the Northern Mass Burial Zone, is on territory now taken up by the Dinamo sports center. The zone borders on a site where the State Sports Training Center for National Teams from the Sverdlovsk Region intends to build a new biathlon complex, named after Olympic biathlon champion Anton Shipulin.

The deputy director of the regional Sports Training Center, Yury Leonov, insisted to Current Time in 2020 that no map of the burial sites was found in any government archive or offices. “If [activists] find something there, then, we, of course, will stop the construction,” Leonov said.

27 Years Without Yekaterinburg’s Masks Of Sorrow

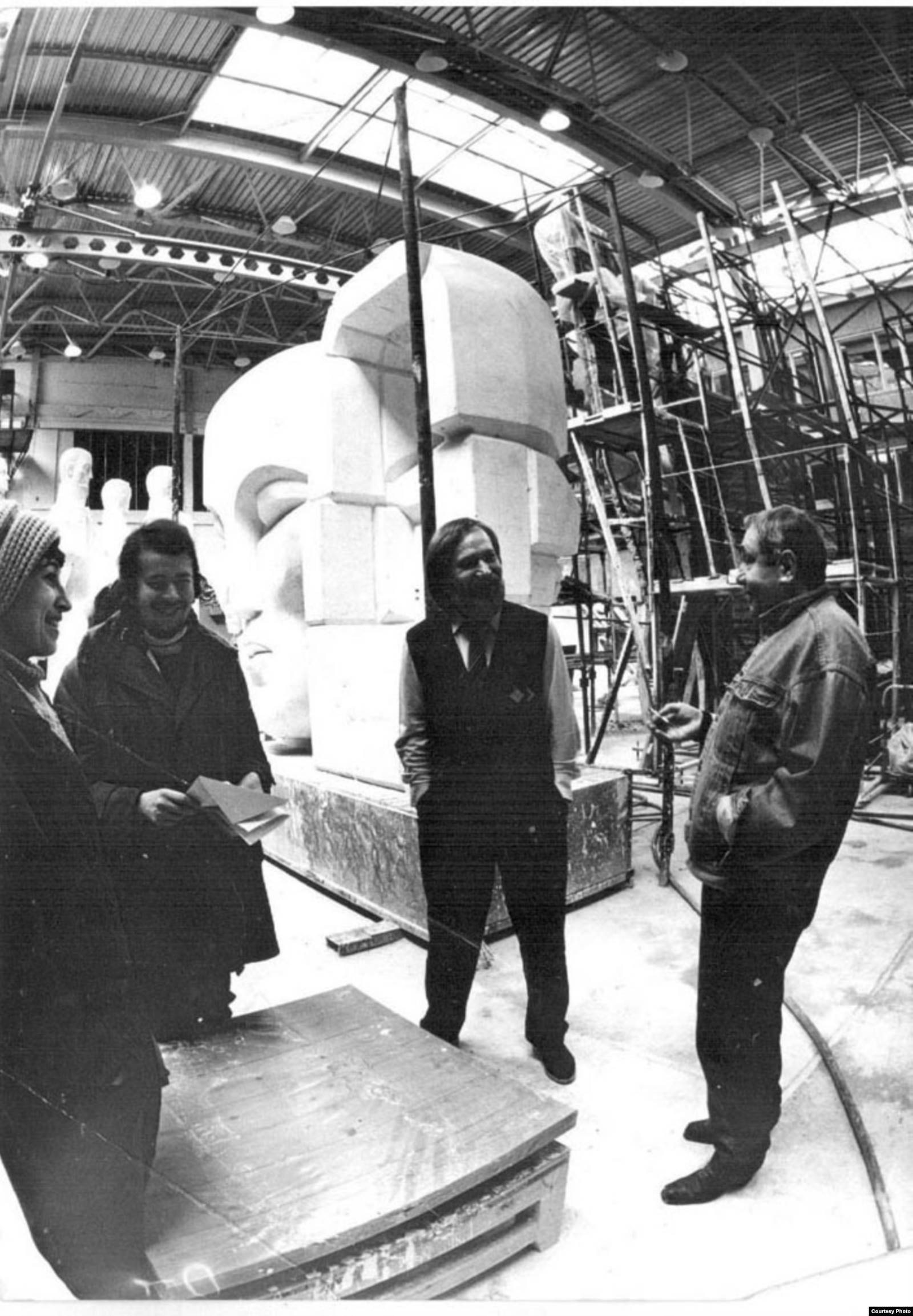

In 2017, Masks of Sorrow, a monument by Russian sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, a native of Yekaterinburg, was erected on the grounds of the memorial complex. Since the early 1990s, the Yekaterinburg Memorial Society, which first invited Neizvestny to discuss such a memorial, had attempted to shepherd the project to conclusion.

It proved a daunting, long-term campaign.

On April 24, 1990, Sverdlovsk’s Memorial community, the Sverdlovsk City Executive Committee, and Neizvestny concluded an agreement about creating a memorial for the victims of the Stalin repressions in the Urals. The work was supposed to be a continuation of Neizvestny’s Triangle of Suffering project to preserve the memory of these victims with Masks of Sorrow monuments in Magadan, Yekaterinburg, and Vorkut.

The Magadan monument opened in 1996, some 21 years before Yekaterinburg’s.According to the Masks of Sorrow agreement, a copy of which Current Time has, Neizvestny initially undertook to create a 15-meter-high (49-feet-high) granite high relief for $700,000.

Point 10 of the agreement specifies that Neizvestny would transfer his payment to a fund for the construction of a memorial to Sverdlovsk’s victims of repression.

From the start, it was planned to erect Neizvestny’s sculpture in front of the Palace of Youth, a center for performances and cultural events for Yekaterinburg’s young people.

However, after the collapse of the USSR, problems with financing began. Funds existed for only 50 granite blocks to be used to build the sculpture, rather than 3,500.

Yekaterinburg Memorial Society leader Pastukhova personally met with Ernst Neizvestny and convinced him to stay with the project.

Nonetheless, plans for the Masks of Sorrow remained in limbo until 2013, when the Ernst Neizvestny Art Museum opened in Yekaterinburg.

After long discussions, the city’s authorities agreed with the sculptor that the memorial would be made out of bronze and stand 3 meters (roughly 10 feet), rather than 15 meters, tall. The owner of a local private foundry, Ivan Dubrovin, paid for the sculpture to be covered in bronze.

In 2016, Ernst Neizvestny died and negotiations about the memorial continued with the sculptor’s widow, Anna Grem.

“These were complicated, lengthy negotiations; especially considering that Neizvestny had rather tough conditions,” recollected ex-Yekaterinburg Mayor Yevgeny Roizman. The American-Russian sculptor's concerns focused on the sculpture's materials, size, and scale.

“At least, that’s how it turned out," Roizman continued. "You have to understand that the Yekaterinburg authorities, from the start, were sympathetic to restoring the memory of victims of political repressions. For precisely that reason, a memorial complex appeared here in 1996; one of the first in Russia.”

In November 2017, Yekaterinburg’s Masks of Sorrow finally opened in a formal ceremony. Local officials organized a press-conference for the event. But here, too, controversy arose.

Svechnikov reports that the local government initially invited then Memorial leader Anna Pastukhova to the press-conference, but then, within a few days, disinvited her, with apologies.

“They said that they were told that Memorial should not be at this press-conference," Svechnikov recollected. "As a result, Pastukhova went there as a visitor, although she should have been present as a speaker at this event. Indeed, for more than 20 years, the city officials themselves hadn’t executed the agreement, but Yekaterinburg Memorial had urged them to expedite the sculpture’s creation, and had written requests, and talked with Ernst Neizvestny.”

The sculptor, Svechnikov stressed, had flown to Sverdlovsk in 1990 to discuss the project “because Memorial had invited him, and not because our administration attempted to do something.”

The city itself has not acknowledged any such neglect.

Yekaterinburg's news portal, however, omitted all mention of Memorial in its coverage of the Masks of Sorrow opening. Rather, attention focused on government guests, who did not stint in their recollections of Stalin’s victims.

“This is a significant event in the life of the region and Russia. Tens of thousands of people from the Urals suffered in the years of mass repressions …” stated Governor Yevgeny Kuvashev. “The erection of the monument is a tribute to the memory of the victims of political repressions, to all those who innocently suffered from the actions of the totalitarian regime.”

Battling On From A Basement

In the 1990s, commented Memorial activist Svechnikov, “respect for Memorial was so high that it was unseemly to request money from the organization.”

For an office, the Yekaterinburg city administration instead provided the organization with a large room in a building on downtown Vayner Street. Lectures and seminars took place there, and children of the repressed spoke at events.

The city provided the room free of charge “as a token of their respect” for Memorial, claimed Svechnikov.

President Boris Yeltsin, another Yekaterinburg native, was among Memorial’s members and a member of its Public Council until his death in 2007.

But in the 2000s, as official attitudes toward independent civil society groups hardened, the city government’s treatment of Memorial reportedly began to change.

When the city decided that Memorial’s room needed to be restored, Memorial was removed from their free office in the Vayner Street building. Unable to pay the rent for the restored facility, they instead moved into a basement room the city offered, and did the necessary repair work themselves.

‘Hello, We’re A ‘Foreign Agent’'

Outreach had always been part of the work of the Yekaterinburg branch of Memorial, whether working out of a basement or a regular office. As a professional teacher, Anna Pastukhova held multiple lectures, exhibits, and met with schoolchildren to explain the organization’s work investigating the human rights violations of the past.

But in 2015, the Justice Ministry deemed the Yekaterinburg Memorial Society a “foreign agent” for supposedly using foreign funds to influence Russian public opinion.

Dozens of non-governmental organizations, independent media outlets (Current Time and Current Time’s parent, RFE/RL, are considered “foreign agents” in Russia), and individuals also have been designated “foreign agents” in what rights activists consider a crackdown on criticism of the government.

The “foreign agent” label made Memorial’s work more difficult, especially in schools.

In 2017, Sverdlovsk regional Education Minister Yury Biktuganov distributed a letter to schools that stated that “the content and methodology of [Memorial’s] individual events are ambiguous and can exert a negative influence on the upbringing of the younger generation.”

At the end of the letter, a copy of which Current Time has, the minister advised school principals to restrict the opportunities for teachers and students to take part in such events.

“We came to schools many times after this and said, ‘Hello, we’re ‘foreign agents.’ We want to co-host such and such an event,’” said the current head of Yekaterinburg’s Memorial group, historian Aleksei Mosin, who was elected as chairman after Anna Pastukhova died from COVID-19 in May 2021.

“Of course, people were already looking at us sideways and weren’t ready to participate in something like this. So, now, we don’t do such experiments.”

No Plaque, No Memory? As part of its effort to preserve the memory of Stalin’s political victims, the Yekaterinburg Memorial Society is conducting a city project called Last Address. Activists put up plaques on Yekaterinburg buildings from which, in the 1930s and later, the secret police seized residents and ultimately deprived them of their freedom forever.

In 2019, unknown individuals stole eight of these plaques. Memorial announced a fundraising drive to create replacements for them.

In 2021, seven new plaques, installed in April, were stolen the day after their installation. Mosin, though, is determined to continue the work Pastukhova began: For instance, the organization is seeking to install a memorial plaque at 17 Lenin Avenue, the city's former NKVD headquarters, where the repressed were shot.

“But if this wave of confusion [over Memorial] rises, it’ll take us with it as well,” he cautioned, in reference to the court cases in Moscow. “Will the local authorities suddenly show initiative and liquidate our organization?”

With the future unclear, Mosin can only express solidarity “with our colleagues” and hope that “the people” behind prosecutors’ attempt to close Russia’s two Memorial organizations “will come to their senses, after all.”

Find Out More:

Generation Gulag

Generation Gulag is a series of 12 short films created by the non-profit media organization Coda Story and broadcast by Current Time. The series documents the stories of survivors of the Soviet gulag, or labor-camp system.