Many Afghans describe their recollections of the 1996-2001 rule of the Taliban in terms of fear and terror. Now, with the extremist Islamist group’s territorial control expanding following the departure of most U.S. and NATO troops, these residents dread a return to the past.

The extremist Islamist Taliban group, considered terrorists in some countries, took complete hold of power in Afghanistan in 1996 and proclaimed an Islamic emirate. They introduced sharia law, strictly limited the rights of women, introduced the death penalty and corporal punishment. During this time, an enormous part of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage was also destroyed. The Taliban remained in power until shortly following U.S. troops’ invasion in October 2001. They then launched an insurgency.The group’s comeback gained momentum this spring, after it stepped up its military attacks, eventually taking control over a significant part of Afghanistan. These developments followed the announcement of a February 2020 peace agreement with the Taliban about the withdrawal of U.S. troops by September 2021. In some of their captured territories, the Taliban re-introduced sharia law and executed Afghan troops, despite the peace agreement’s terms and the Taliban’s promises of moderation.

In recent months, tens of thousands of people have fled the country. Those who remain fear a return to the years when the Taliban was in power. In this article, Current Time shares the stories of some of those Afghans who lived under the Taliban in the 1990s, and how they view what is taking place in their country today.

‘I Spent My Youth Terrified’

When the Taliban seized power in 1996, Wahida was working in the Afghan government and studying in a university in Kabul. To this day, she remembers that time with trepidation.

Out of fear for her life, she did not give her full name and has concealed some details of her biography. The strict laws that the Taliban adopted led to the young woman quickly losing her job. She could not finish her studies. Today, Wahida is a homemaker and raises her daughters. Her husband does not want her to work. Wahida recalls that her father had to marry her off because of the worsening situation for women’s rights and fears for his daughter’s safety.

“Some of my friends were married against their will because it was dangerous to be a single girl in Afghanistan. Because of this, my family married me off as well,” recollects Wahida. “After [the Taliban came to power,] the most awful days in my life began. Even the Taliban’s faces scared me. I could no longer go to work. Even going out onto the street was difficult.”

Immediately after the Taliban came to power, the Islamist group severely restricted women’s rights. They were forbidden to work in any economic sector apart from health care, to visit educational institutions, and even just to go out onto the street without the accompaniment of a male relative. It was particularly difficult for women who had become widows during the Afghan war and were compelled to support themselves and their children on their own.

In public, women also were obliged to wear a burqa, a type of clothing that completely covers a woman’s body, hair, and face. Makeup, shoes with heels, beauty salons, trips on public transportation with men who were not related to them were banned.The Taliban punished women for “defiant behavior,” which could mean anything that did not correspond with the Taliban’s ultraconservative interpretation of the Koran. In response to calls by the United Nations and Western countries to rescind adopted decrees about women’s rights and return to Afghan women at least access to education, the authorities declared that this will lead only to depravity and the destruction of the country and Islam. “I was terrified all the years of their rule. I remember how the Taliban beat women, how they forbade girls to study. Because of them, I couldn’t receive a higher education and realize my dreams,” said Wahida. “The most terrifying thing was that women were compelled to wear a burqa. I never wanted to dress the way the Taliban wanted.”

In 2001, after the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States, U.S. President George W. Bush sent troops into Afghanistan to rout out the Al-Qaeda militants whom the Taliban had harbored and provided with territory for training camps, and to remove the Taliban from power. The Taliban government fell within two months of the invasion, in December 2001. Politician Hamid Karzai, who annulled a large part of the Taliban’s bans, was placed as the head of a transitional government. “With the end of their rule, it was like I started to live again,” remembered Wahida. “I went out onto the street without fear, I wore what I wanted. Islam is a religion of peace, not violence, but the Taliban showed the world otherwise.”

With the signature of the February 2020 peace deal with the U.S. and the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, the Taliban began to attack government buildings, military bases and conquer territory. Before the agreement was concluded, the Taliban’s political wing publicly declared a more “liberal” approach to women’s rights. The group promised not to try to tighten the law in this area and to take into account women’s interests in education and working.

But, despite these promises, in Afghanistan’s Taliban-controlled northern provinces, women again are forbidden from leaving their houses unaccompanied by a man and are required to wear hijab. In some regions, which the Taliban also controlled earlier, women were permitted to receive an exclusively religious education. “I spent all of my youth terrified. I don’t want young people -- girls, in particular – to be deprived of their rights,” said Wahida. “I only have one wish – that the girls of modern Afghanistan never turn into girls from the time of the Taliban.”

Wahida wants her daughters to receive an education and later be able to find a job. But if the Taliban again comes to power, then, together with her family, she’s prepared to leave Afghanistan.

‘I Didn’t Fear For Myself, But For My Wife And Daughter’

Abdul Naeem Akakhel had just turned 20 when the Taliban came to power in September 1996. During their more than five years in power, he experienced both poverty and loneliness. All of his family fled Afghanistan.

“All of my brothers and sisters managed to leave the country, but I couldn’t. I had to stay,” recounted Akakhel. “[During the Taliban’s rule,] I survived poverty, hunger, and unemployment. On the days when the fighting intensified, I had to hide in the courtyard to avoid being killed if a rocket hit [the house].”

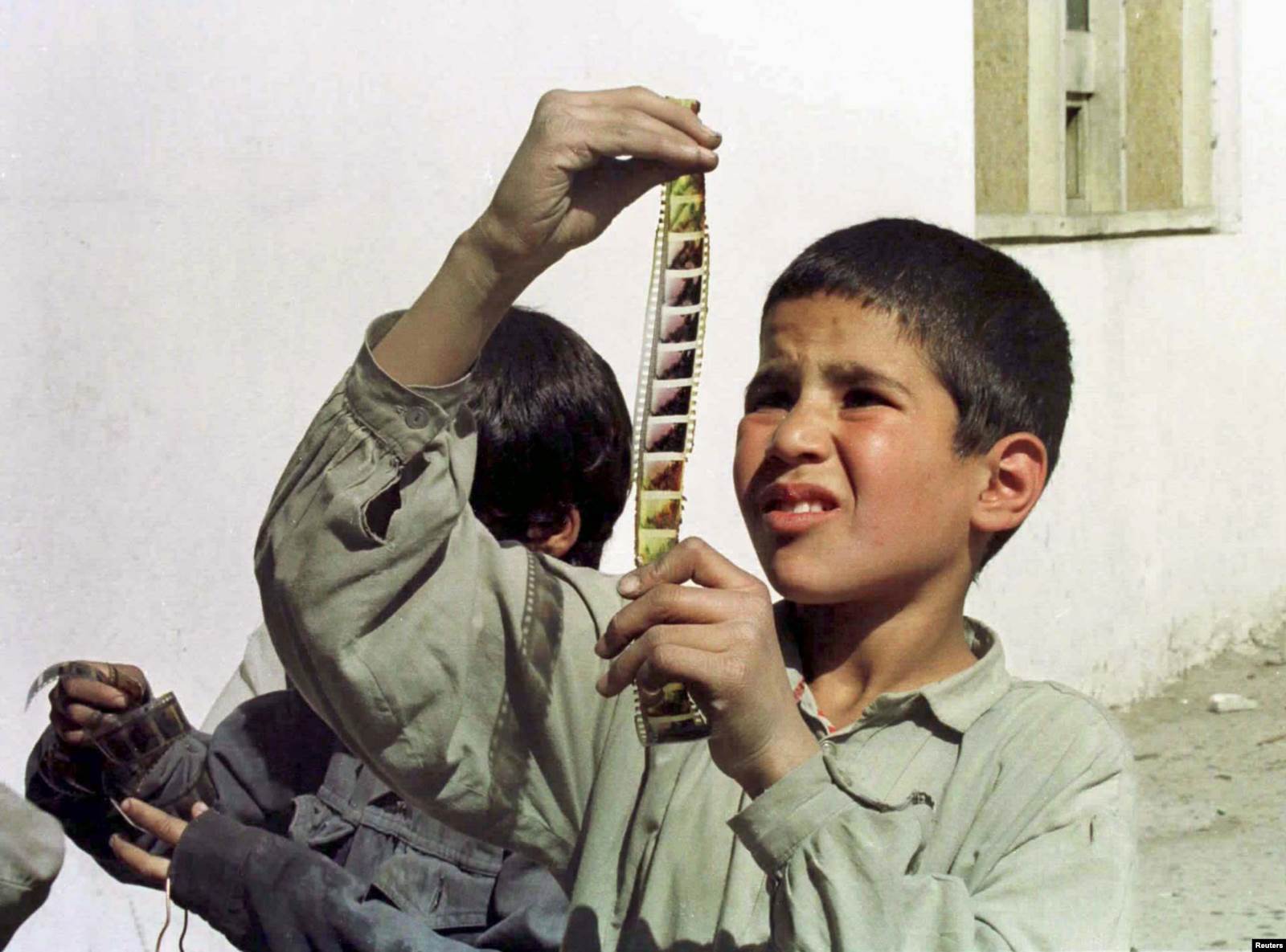

Under Taliban rule, many commonplace types of entertainment were forbidden, and an enormous part of the country’s cultural heritage was completely destroyed. Taliban supporters considered art, in general, to be a manifestation of heresy. In less than six years in power, national monuments, museums, libraries, art collections were destroyed; tens of thousands of film reels and books were burned.

The Taliban banned a wide-ranging assortment of non-religious celebrations, music, cinema, and television. Akakhel says that this ban affected his personal life also. “My wife and I dreamed about a big and chic traditional wedding, but, according to the law at that time, it was forbidden to even turn on music. Therefore, only several people were at the wedding, and we didn’t have any kind of ceremonies,” he recalled.

Not long before U.S. troops entered Afghanistan in October 2001, Akakhel found a job in the International Migration Organization. Though various international humanitarian organizations in this period could continue to work in Afghanistan, their Afghan employees or their families often became the victims of attacks by Taliban supporters. Akakhel worried especially about his family then.

“I had to both work and protect them. This is very difficult. I was afraid more for my wife and daughter than for myself because, at that time, it was just impossible for women to live without men,” he recalled. “Sometimes, when I had to stay at the office at night, I requested my relatives to stay with them so that they wouldn’t be killed.”

In Akakhel’s opinion, the Taliban began to mobilize their forces even in 2014, when the U.S. first began to withdraw its troops. He does not believe in the Taliban’s reforms or in their promises of more moderate policies. “You can expect anything you like from them.”

‘I Saw Them Cut Off A Man’s Arm And Leg’

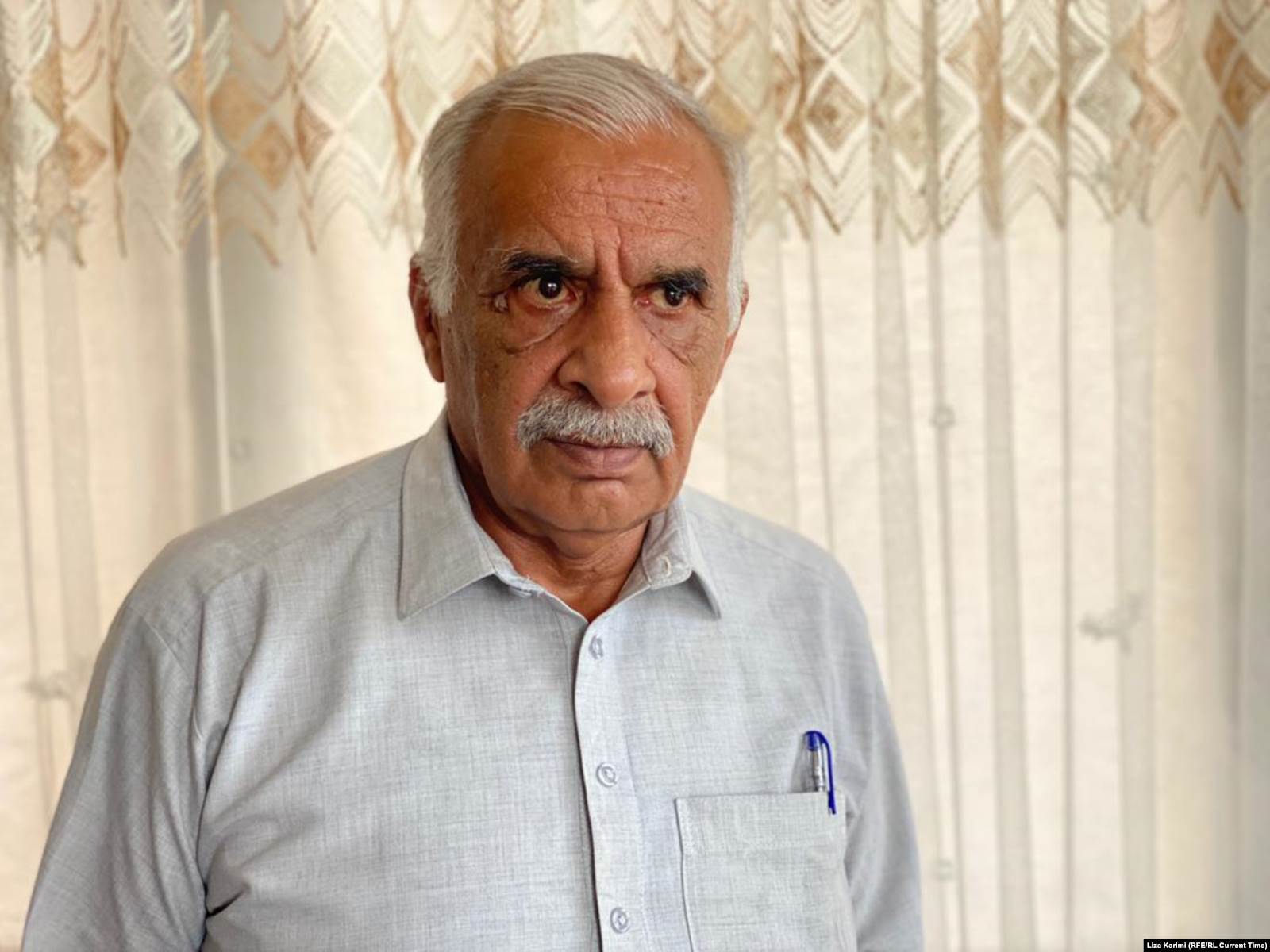

In the spring of 2021, Mohammad Akhtar retired from the Ministry of Finance, where he had worked for a large part of his life. He was an employee there as well when the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan. In 1996, he lost his job and was forced to trade at a market.

“To feed my family, I had to sell vegetables. My wife could no longer work, so I was the only one left working. Sometimes, my daily earnings weren’t enough,” Akhtar remembered. “The children went to bed hungry. Sometimes, we had one piece of bread (naan) for the entire day.”

Under the Taliban, harsh punishments were introduced for violating the law. Depending on the severity of the “violation,” people could be whipped or have a limb cut off; for more severe violations, people were executed. Ethnic minorities living within Afghanistan also become murder victims.

The religious police then patrolled the streets. It was made up almost entirely of young people who carried long sticks, whips, or Kalashnikov assault rifles. If they considered that one person or another was violating public order or the law, they had the right to use force, said Akhtar.

“We didn’t have freedom of speech. No one lived the way they wanted to. And if there were such [people], then they punished and executed them,” he recounted. “There were a lot of executions. Everyone lived in fear.”“I remember the moment when I saw them cut off a man’s arm and leg,” he continued. “They beat men and women. The situation turned into a nightmare for everyone. At night, I was scared, and during the day I did everything that they wanted, even if it was against my own will.”

Mohammad Akhtar has three daughters. They could not get an education because of the Taliban and, like their mother, were denied the chance of helping their father earn money. Like many other residents of Afghanistan, his daughters do not want to return to those times, according to Akhtar.

“People have begun to reminisce about times during the Taliban’s rule. We forgot nothing. We won’t be able to survive this another time,” Akhtar said, with genuine fear in his eyes. “We don’t want this [situation] to happen again. We want a peaceful life. Our people are tired of this.”

--Translated by Current Time English Editor Elizabeth Owen from "Вся моя молодость прошла в ужасе". Жители Афганистана вспоминают жизнь при "Талибане."

See Also:

Why Russia Has An Ear For Taliban Talks

As the Islamist Taliban movement searches for “international legitimacy” following substantial territorial gains in Afghanistan, it has found a willing partner in Russia, regional and security experts say.