The territorial conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh has lasted since the end of the 1980s. As a result, more than a million people from both countries are estimated to have become refugees and forced migrants, losing their homes and their ways of life.

The central characters in photographer Natalia Josef’s story have lived for 30 years in various temporary shelters: in a former Young Pioneers camp in Azerbaijan and in a former school in Armenia. They do not feel at home in these places. Instead, they hold onto memories of their past lives. With those memories, they also try to preserve their identities.

Armenia: The School On Sebastia Street

Yerevan’s Technical School Number 16 was founded in 1963. It is made up of several buildings. Classes used to take place in the building at 3a Sebastia Street. At the end of the 1980s, the building became vacant, and in 1989 the first displaced persons from Azerbaijan began to settle here.

In 2003, the Armenian government sold the Sebastia Street building to the Mkhitar Gosh Armenian Russian International University. After this, some of the apartments were sold.

There are now 56 rooms in the building at 3a Sebastia Street. Refugee families still live in 23 of them.

Most of the refugees at Sebastia Street are from Baku. One woman is from Sumgayit, about 36 kilometers from the Azerbaijani capital. The rest are from the western Azerbaijani city of Ganja, a few hours’ drive from Karabakh.

Rimma And Margarita

Rimma and her 90-year-old mother Margarita occupy one of the rooms in the building at 3a Sebastia Street. Rimma’s two sons live in neighboring rooms.

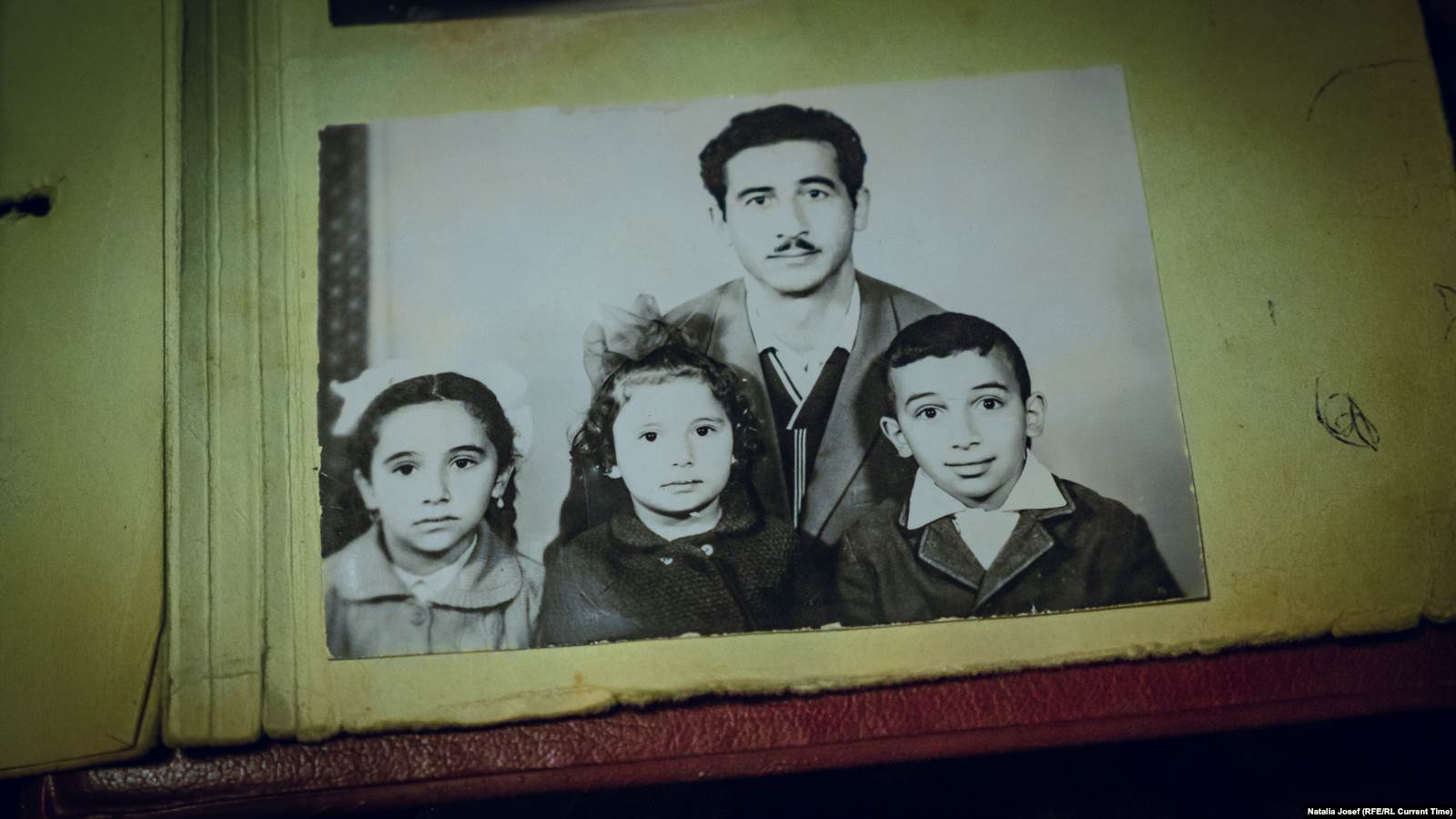

Rimma was born in Baku in 1965. Her mother is also a Baku native. “How many generations [of our family] lived in Baku!” she exclaimed.

Rimma used to manage a machine tool factory’s standardization department. She met her future husband there. They married and had a son. The family had just received a new apartment when massive protests over Karabakh broke out in Baku in November 1988. The demonstrations followed brutal violence against ethnic Armenians in nearby Sumgayit nine months earlier.

"In November 1988, our whole family fled to (Russia’s North Caucasus city of) Stavropol: my mother-in-law, the pregnant wife of my brother-in-law, my husband and I with a 2-year-old child. Mama and papa didn’t live with us. They escaped on their own."The family took only the most necessary things and documents.

"Mama took her things, and then papa put mama’s things into a container,” said Rimma. “They took their own things, and mine, what was there … they didn’t take anything. There’s mama’s photo album from Baku, but I don’t have anything from Baku."

Rimma could probably be called the building’s commandant. She helps stand up for refugees’ rights, arranges their resettlement from the temporary shelter on Sebastia Street.

Zhanna

Zhanna was born in Baku. She talks about how she dreamed of teaching children from the time she was a child. "I loved to death my first school teacher. Seda Nikolaevna Babadjanova was Armenian. I adored her so much that I said that I should be a teacher.""When I was in the 2nd or 3rd grade, she gathered the little ones around her in the [school] courtyard. She placed stools and little chairs there. She sat the children down and she was playing [with them] in school."

Before the war, Zhanna worked in a kindergarten: first in Shusha in Nagorno-Karabakh, then in Baku. After the 1988 violence against ethnic Armenians in Sumgayit, she and her husband and children began to get ready to leave Azerbaijan.

During their time off, the couple traveled to Yerevan to look the city over and find a place to live. At first, they lived with relatives, but after a few days they were given a room in a dormitory.

Nora And Edik

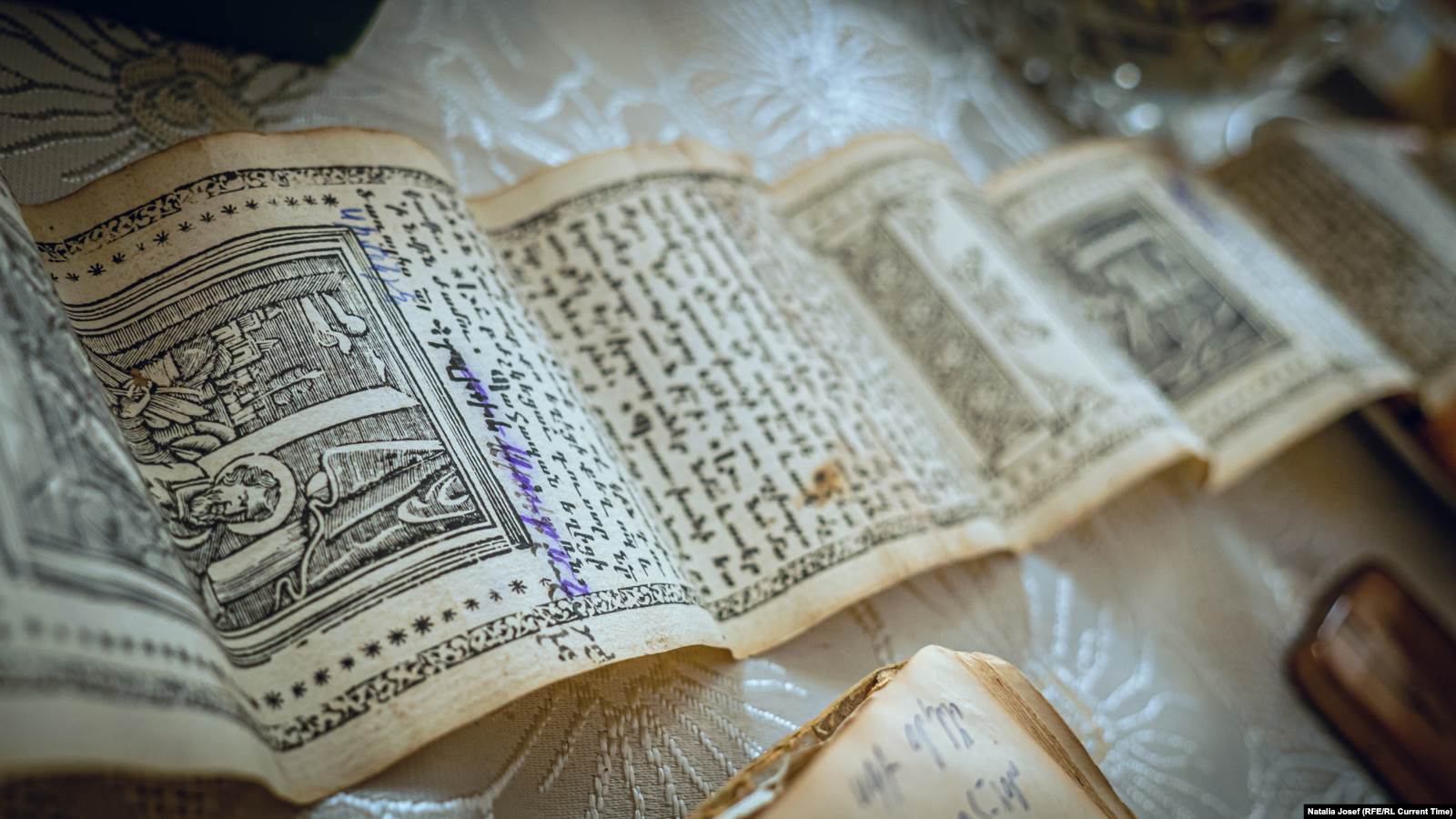

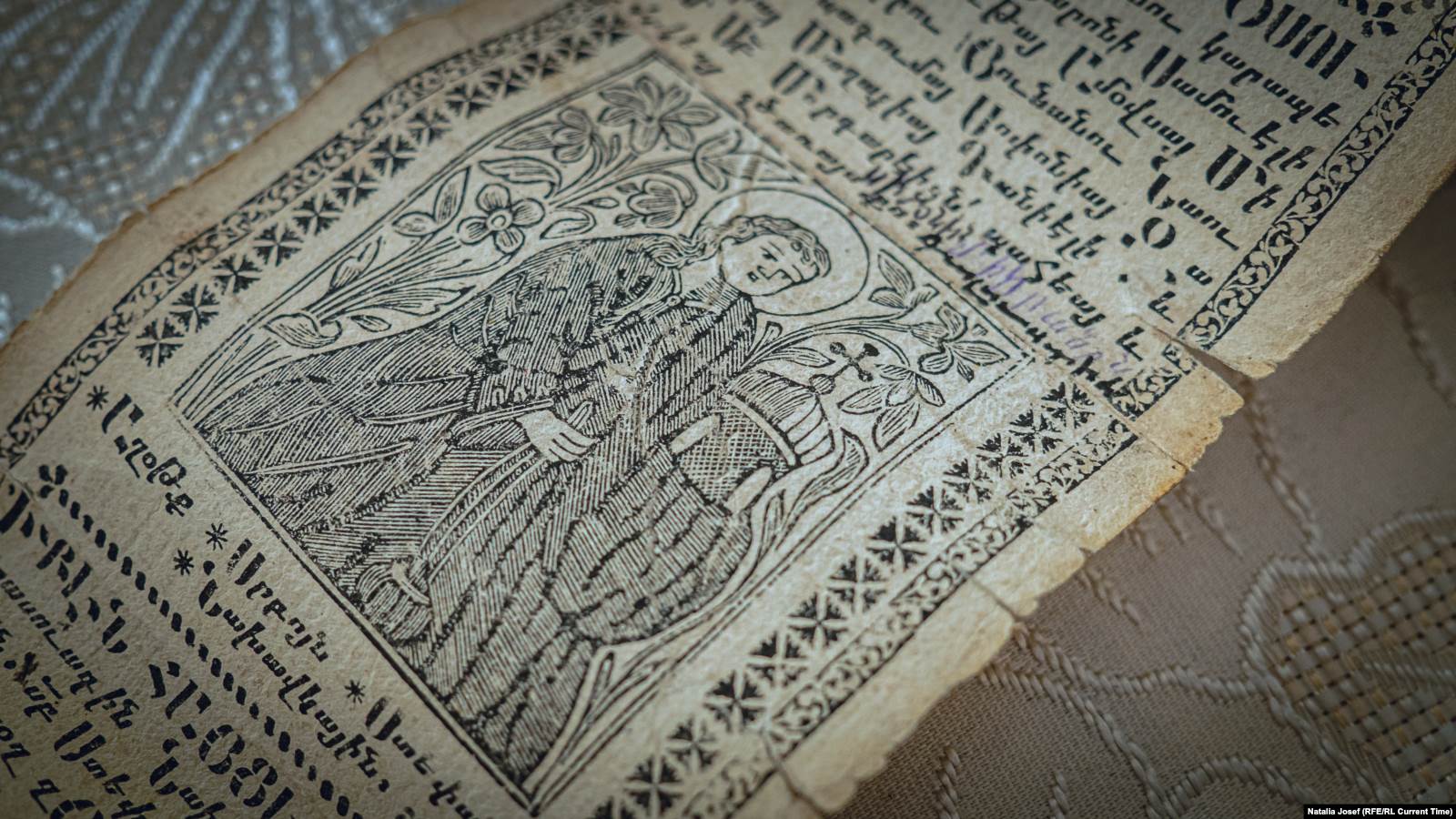

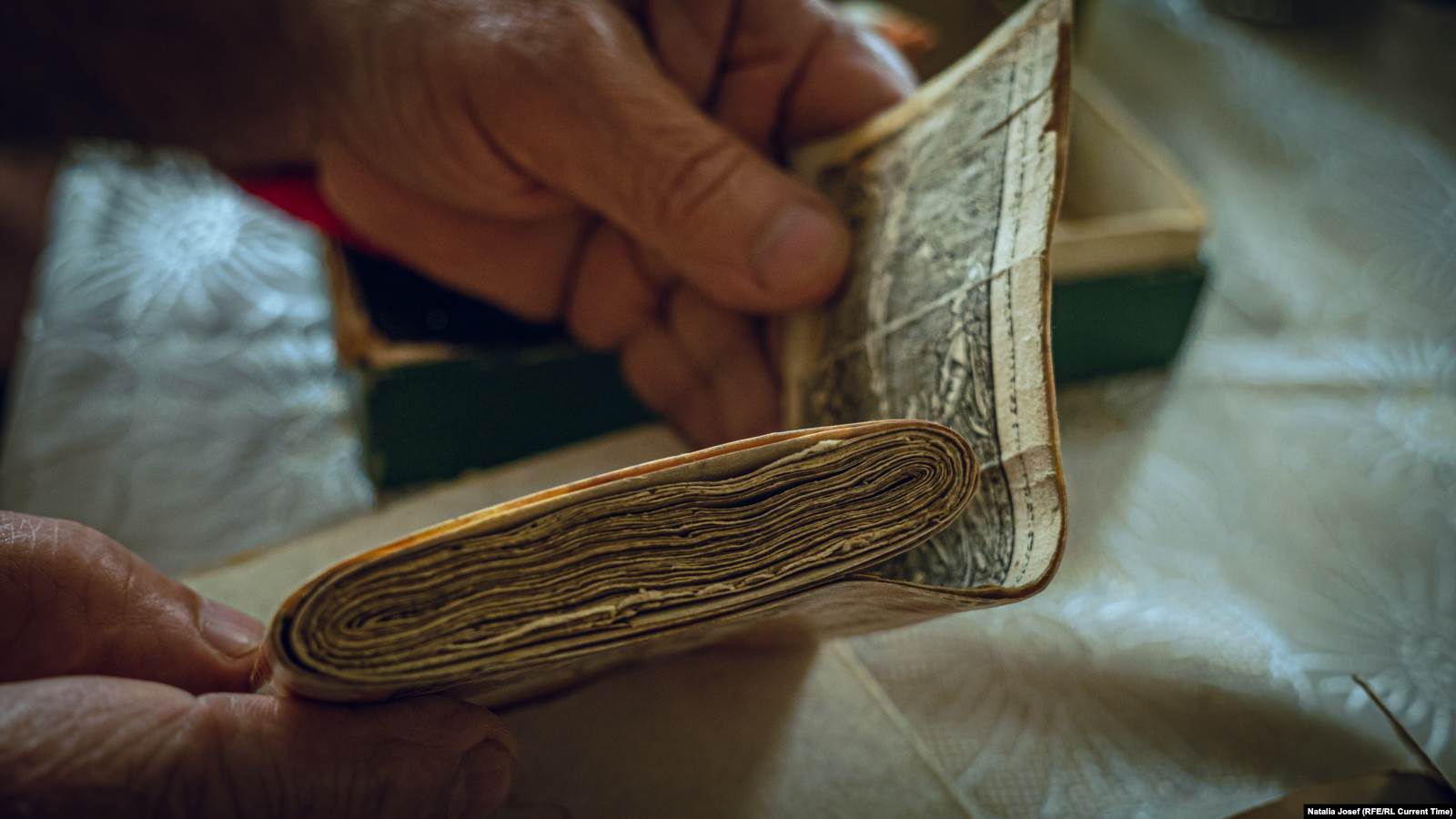

"This is our Bible. My maternal grandfather taught people, got rid of unclean forces and ailments by reading prayers," recounted Edik. "These sacred books were in the family when they escaped from Turkey to Armenia in World War I. They left their wealth behind. They buried seven jars of gold and jewelry there where they lived."

Edik’s family moved to Baku from the Armenian town of Gyumri when he was 5 years old.

Edik met his future wife in an Armenian theater troupe that had come to Baku from Tbilisi in neighboring Georgia. In 1975, they got married and had a church wedding.

"I set a condition for her: If you won’t be baptized, we’re completely different people. I want there to be people with me who share my faith. The first wedding was in Baku, in the Armenian church in the city center."

In 1988, after huge protests began in Baku, they felt compelled to leave Azerbaijan. The couple already had two children then, and were awaiting a third. "When we left Baku, we didn’t have time to take anything," said Edik. "We just picked up and left. We were leaving for the unknown and we didn’t know if we’d reach that place or not."

Two of Edik and Nora’s children now live in Russia. A daughter lives in Yerevan.

AZERBAIJAN : The Former Pioneer Camp Volna

In the 1950s, a Young Pioneer camp called Volna (Wave) opened in the village of Buzovna, a few dozen kilometers from Baku. The children of workers from the Baku Electric Machine Construction factory vacationed here in the summer; gatherings of Young Pioneers took place here in the winter.

Volna’s 10-minute proximity to the Caspian Sea was one of its attractions. Aside from residential buildings and a cafeteria, the complex came with a library, a soccer field, an open-air cinema, gazebos, spaces to play games, tree-lined lanes, and a water reservoir. Up to 400 children could vacation here at the same time.

In the 1990s, when the first refugees and Internally Displaced People began to settle here, there were still drawings on the walls of the abandoned housing.

Ragim

Ragim served in the army in Russia’s Far East. He returned, got married, and started to build a house. But the war over Karabakh started, and he needed to find a place where he could flee with his family. Then he remembered Volna, on the shore of the Caspian Sea.

"I moved here with my family. We had three small children. And now there’re four of them."

The family managed to bring to Volna most of their personal things and part of their livestock. Ragin also took with him a cherry-plum walking stick he’d made in 1985. "Then, it was straight, but it has become twisted with time. It had to be recut."

“I was the first [to move to Volna]. Then, my uncle came here, my uncle’s brother … Everyone here, basically, is a relative. Many of them from Lachin.”

Thirty-seven families of Internally Displaced Persons from Shusha and Khankendi in Nagorno-Karabakh (called Shushi and Stepanakert in Armenian), and from the region of Lachin, now held by Armenian forces, live on the camp’s grounds.

Ragim is the commandant of this place. “I’m almost 60 years old, and I’ve become a Pioneer,” he joked. “Since I’m living here, I’m a Pioneer.”

Ismail And Flora

In 1992, when firing began on their native village of Farrash in the Lachin region, Flora’s family was forced to flee, leaving behind their livestock and a large house full of supplies.

In that year, Ismail’s father sent his sister and him to stay with relatives in Agjabedi, a city in central Azerbaijan. The parents themselves remained in the Lachin region.

"They could bring out some things of their own: a samovar, absolutely the bed where they slept. And they took things that they needed to use. But the beautiful things, which were in the cupboard, they didn’t touch" or the cupboard itself, said Ismail.

"They didn’t spoil the house’s beauty. They didn’t think that they were leaving forever. They didn’t know that they were totally leaving. For that reason, Mama said, ‘Let everything stay there.’ They took with themselves only the most necessary things."

There were four samovars in the house. Ismail and his brother took two of them to Volna. "As Lachin natives, we drank tea out of a samovar. My father, even when he was sick, always set up the samovar. Particularly for guests, this was a must. We slaughtered a lamb when we had guests. From one half, we prepared bozartma (lamb stew), and kebabs from the other half."

Flora, like Ismail, is from the Lachin region, but from a different village, Vaqazin. They met and got married in Agjabedi in 1995. The couple has three sons. They named one of them Lachin.

Roksana

"I was born in the town of Agdam. I lived there until I was 10. It was July 23, 1993 when they (Armenian forces) occupied the town of Agdam. Early in the morning, (Azerbaijani) soldiers came to us and said that ‘It’s time for you to leave. They’re attacking the town.'"

"The bombings were frequent, frequent. Many people totally left to go to their relatives’ houses. They emptied the buildings. A few times it even happened that it’d be like we were leaving. We were staying at someone’s house, moved away from the town, and then, again, returned there."

"Mama, my brother, and I: We three ran away. We got dressed quickly, took our suitcases, and left. In my hurry, I even ran out in my slippers. And I returned and put on my shoes. To tell the truth, later, mama, when she got mad, always said, ‘You returned and changed your slippers for shoes. That’s why we didn’t go back to Agdam.’"

Roskana and her mother and brother did not end up immediately in Volna. For a long time, they moved from place to place: to Baku, the Azerbaijani resort town of Nabran, and Russia’s Siberia. "In 1999, we found this Pioneer camp and got set up here. We’ve already lived here for many years."

Roksana’s mother died in 2003, one month shy of her 48th birthday.

"I think that the war took a toll on her. It’s stress: You don’t have an apartment or those living conditions which you’re used to. This all had an impact on her."

All that remains from their home are three photographs of her mother that Roksana got from a cousin. The things that they took from Agdam have already worn out.

This publication was prepared as part of the Memory Guides: Information Resources for Peaceful Conflict Transformation, a project implemented by the Center of Independent Social Research e.V. Berlin. The project is supported by Germany’s Foreign Ministry within the framework of its Expanding Cooperation with Civil Society in the Eastern Partnership Countries and Russia program.

Longstanding differences between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh came to a head in the late 1980s as Soviet populations began to express themselves more freely and challenge the central government. Populated primarily by ethnic Armenians, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast declared in early 1988, with Yerevan’s support, that it was leaving the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic and uniting with Armenia. The 1988-1994 war between Armenia, Karabakhi separatists, and Azerbaijan over Karabakh and surrounding territory led to the deaths of some 30,000 combatants and the flight of hundreds of thousands of civilians.

No member of the United Nations, including Armenia, has officially recognized the so-called Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, declared in 1991. Armenia, however, insists that this territory should be independent from Azerbaijan. In 1993, the United Nations adopted four resolutions that demanded the withdrawal of Armenian troops from Karabakh and recognition of the territory as part of Azerbaijan.

Despite nearly 28 years of diplomatic efforts and negotiations within the framework of the so-called Minsk Group, a trilateral body (co-chaired by France, Russia, and the U.S.) set up by the Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe, the conflict remains unresolved.

Read More:

Azerbaijan's 'Black January': 'Tanks Were Crushing And Shooting At Everyone'

Thirty years on, 76-year-old Baku resident Emilie Ragimova still remembers January 20, 1990 in two colors -- red and black. After a night of indiscriminate violence by Soviet troops that left a...

Gorbachev's Ex-Spokesperson: 1989 Uprisings Accelerated USSR Collapse

The upheavals of 1989 that led to the collapse of eastern Europe’s communist governments would prove to be precursors of the USSR’s own collapse, but, at the time, this was far from clear. To find out firsthand how then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev interpreted the destruction of the Berlin Wall and Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, Current Time spoke with Andrei Grachev, Gorbachev’s press secretary from August – December 1991.