‘Schnapps Was Given Out On The Second Day Of Shooting’: The Babyn Yar Tragedy As Described By The Executioners, Their Accomplices, And Survivors

Yom Kippur, the Jewish high holy day of repentance and atonement, fell on September 29 in 1941. This same day, the execution of more than 33,771 Jews in Nazi-occupied Ukraine began at Babyn Yar, a ravine on the outskirts of the main city, Kyiv. The bloodshed would come to be known as one of the most tragic events in Kyiv’s history.

The executions of thousands of innocent people at Babyn Yar would continue for two more years, until Soviet forces regained control of Kyiv.

Working in the archives of the Ukrainian Security Service, the authors of this article examined interrogations about the September 29-30, 1941 massacres recorded by the Soviet Union’s NKVD, or secret police, during World War II and by the agency’s successor, the KGB, up until the 1990s.

(This article contains content that some readers may find disturbing.)

Witnesses Of The First Shootings

The first shots heard in Babyn Yar occurred on September 20, 1941, the day after Nazi troops entered Kyiv. The shooting continued until November 4, 1943, when, a few days before the Red Army’s arrival, Kyiv residents who had not obeyed the order to evacuate the city were killed.

Witness Ivan Yanovych, who lived within the immediate vicinity of Babyn Yar (on today’s Olzhycha Street, then called Babyn Yar Street) told an NKVD investigator on November 15, 1943 that Nazi Germany’s armed forces began executions at the site within a day of taking control of Kyiv.

“The Germans entered Kyiv on 19.IX.1941 (September 19, 1941), and on 20.IX.1941 (September 20, 1941) they had already taken groups, primarily made up of Soviet prisoners of war, to be executed at Babyn Yar, located 800-1,000 meters (roughly half a mile – CT) from my house. I, personally, wasn’t watching how they were executed because there was a guard standing [there] and they wouldn’t let [others] get close. The only thing heard was (sic) people’s cries and automatic gunfire.”

The first shots heard in Babyn Yar occurred on September 20, 1941, the day after Nazi troops entered Kyiv. The shooting continued until November 4, 1943, when, a few days before the Red Army’s arrival, Kyiv residents who had not obeyed the order to evacuate the city were killed.

Nadezhda Gorbacheva, who lived on the nearby Tyraspolska Highway (today, Volodymyra Salskoho Street) , also testified that Kyiv’s Jews had been executed before September 29, 1941:

“….On September 22, 1941, I saw how, during the course of the day, around 40 trucks in which there were Jewish men, women, children, and even women with infants went to Babyn Yar.

I and a series of other women from our [apartment] house moved closer to the place where the Jews were removed from the vehicles. We even crawled several dozen meters to see what would happen next. The other women and I saw that the Germans ordered the transported Jews to undress 15 meters from Babyn Yar, and then the stripped-naked people ran toward Yar, where they were shot. Machine-gun fire was heard and individual shots. I saw how the Germans were throwing infants into the ravine. It was noticeable that many people fell wounded and children were still alive…”

Soviet prisoner of war Leonid Ostrovsky, an inmate in the Syrets labor camp run by the Nazi Sicherheitsdienst intelligence agency not far from Babyn Yar, gave this testimony on November 12, 1943:

“….On September 25, 1941, I was detained by the Germans in Kyiv and sent to the camp for war prisoners located along Kerosinnaya Street (today, Sholudenka Street – CT) ….

From September 28, 1941 until I left the camp (on October 3, 1941 – CT), all the Jews in it up to 16 years old and older than 35 years old were daily loaded into vehicles and taken out of the camp. Soon, these same vehicles came back to the camp without people, but only with clothing that was stored in separate facilities. Therefore, it became known to people in the camp that they’re not transporting everyone in the vehicles to work, as the Germans at first tried to explain, but to an execution.”

After several meetings, senior commanders of the German armed forces and leaders of the Nazi special services planned a “big action” in Kyiv. On September 24, 1941, the first explosions on the city’s Kreshatyk Street, a main thoroughfare, rang out and

a large fire killed many Germans and Kyiv residents. Before the Nazi occupation, buildings in the city’s downtown had been mined by the Soviet military, who subsequently began to blow them up remotely. The Nazis, however, blamed the explosions on the Jews and not Soviet saboteurs.

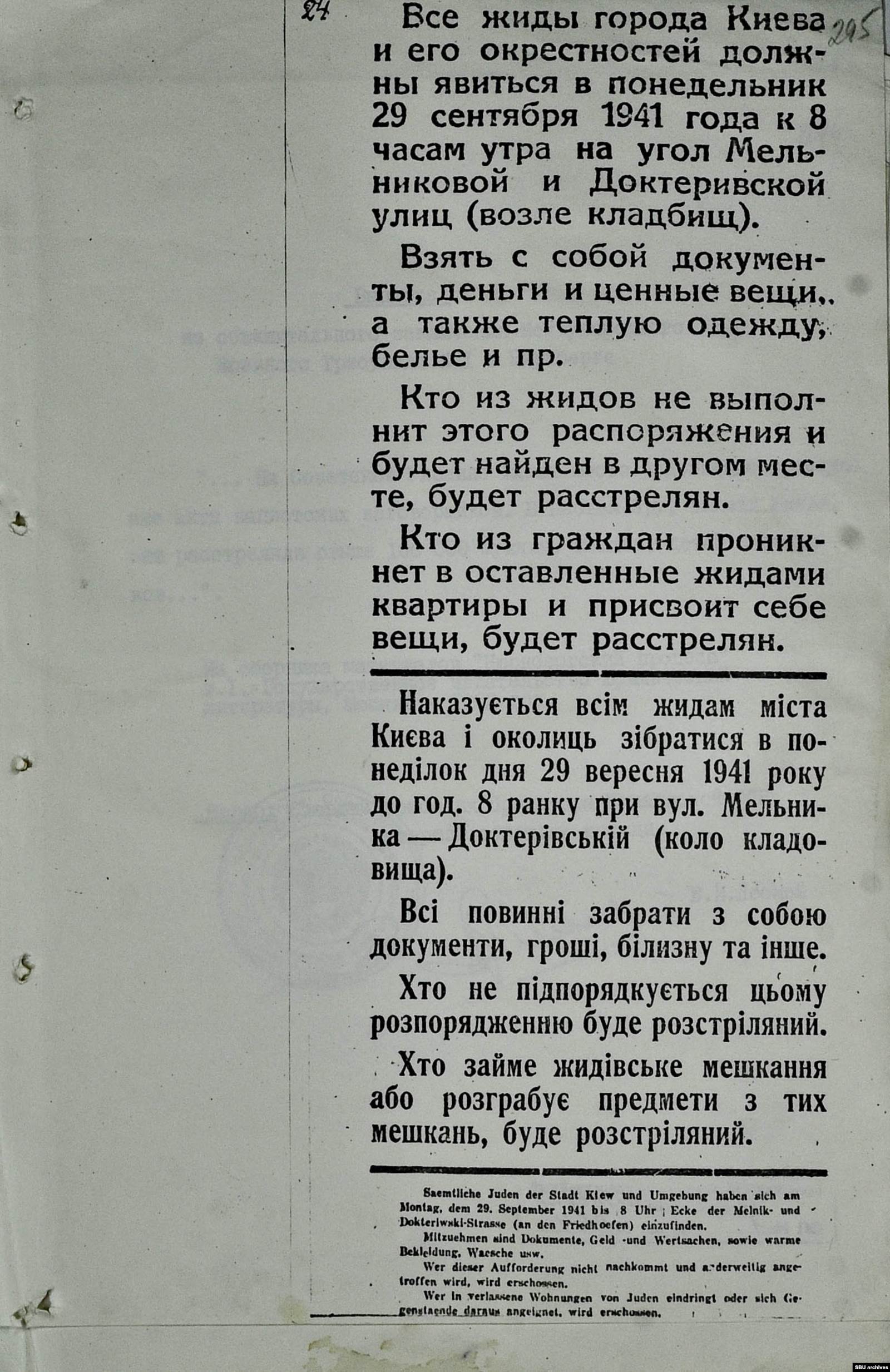

On September 28, an order was distributed throughout Kyiv that the metropolitan area’s entire Jewish population should gather in Kyiv’s outskirts, near a cemetery. They needed to take with them their identity documents, money, and personal items. For this reason, many people did not guess what awaited them. The majority thought that they would be resettled in a different location.

To describe what, in reality, happened at Babyn Yar on September 29-30, 1941, we’re publishing the testimony of the executioners, their accomplices, and victims who managed to save themselves.

‘The Jews Approached The Pit In A Single File’

Three police and SS (Schutzstaffel or “Protective squadron”) units, making up a total of 1,500 men, participated in the shootings that started on September 29, 1941: Sonderkommando 4a (Special Unit 4a) from Einsatzgruppe C (Deployment Group C, an SS unit that carried out mass killings); the Sud (South) police regiment, made up of two police battalions; one company of men from an SS battalion; one police platoon.

The Nazis conducted the shootings with their characteristic meticulousness and attention to order. In two months of war with the USSR, they already had acquired a fair amount of experience in carrying out such executions. For this reason, even in post-war interrogations, they described their actions nearly like everyday events.

SS Obersturmfuhrer August Hafner, a Sonderkommando 4a officer, described the method of killing:

“ …. The Jews approached the pit in a single file. They were supposed to kneel there and in such a way that their back bent over toward their knees, their head was bent down, and their arms were folded.

They were shot at close range with an automatic either into the back of the head or the cerebellum. After the first Jews were shot, others came to the pit in a single file. They were supposed to kneel in the empty places left by those already shot and were shot in the same way.

That’s how the bottom of the hollow was filled up. After the bottom of the hollow was full, the shooting continued in such a way that they were shot in this pit, layer by layer. The shooters were standing on the corpses. The Jews, who were approaching the pit in a single file, could see the shooting from the side of the pit. They went without resistance to the pit and were shot in the way described above.”

The concept of such a mass execution, where the victims were shot and stacked in layers, belongs to "the Highest Fuhrer of the SS and the Rusland-Sud (Russia-South) police,” SS Obergruppenfuhrer Friedrich Jeckeln. He himself cynically called it “packing sardines.”

In his interrogation, August Hafner noted that “By evening, the execution was finished. This could have been between 5 and 6 p.m. … The next morning, the execution continued.”

Before the start of the shootings, when announcements about the mandatory round-up of the entire Jewish population were hung throughout Kyiv, the Nazi special services calculated that around 5,000 – 6,000 Jews would turn up at the designated collection point.

But more than 33,000 people came, and the Nazis proved unable to shoot so many people in a single day. The interrogations show that the killers followed their “work schedule.”

Toward evening on September 29, they stopped the shootings and headed off to rest. But what was to be done with those thousands of Jews whom they hadn’t managed to kill in time? They postponed their death for several hours and left them to wait for morning.

Based on approximate estimates, around 22,000 Jews were shot on the first day. Those who remained, about 11,000 people, the Nazis decided to lodge in garages not far from Babyn Yar (on Lagernaya Street, now Dehtiarivska Street).

The Nazi leadership had decided that, despite the firing squads’ “experience” and preparation, it was necessary “to de-stress” somehow after mass shootings. In a post-war interrogation, former police brigadier Georg Biedermann recounted that “….Before the start of the punishments, I should get food ready for everyone -- particularly for the platoon of SS troops. A large amount of alcohol, including rum, cognac, and champagne, was obtained.”

The following evidence was given by a former Sonderkommando 4a chauffeur, Kurt Werner:

“…On this day (September 29, 1941 – CT), the shootings continued until approximately 5 or 6 (17:00 or 18:00). Then, we returned to our apartment. This evening, schnapps was again given out. We were all glad that the shooting was over…. Also, on the second day, after the shooting, schnapps was given out. I also know that the officers got drunk in the evening.”

But the schnapps did not calm everyone down. Some soldiers could not take what had happened anymore, recalled another Sonderkommando 4a chauffeur, Viktor Trill:

“…. We didn’t have that many people die. I know only two Schupo [soldiers] (the Schupo or Schutzpolizei were police guards – CT), who were shot in their sleep by a colleague since his nerves gave out because of the shootings. This person who fired the shots was given a kind of reprimand …. When I returned from vacation, I was informed that both of the comrades who had been shot were buried properly with military honors, while the madman, who shot himself, was buried somewhere. At the time, all our nerves were haywire … After the shootings, I couldn’t eat for three days my nerves were so worn out ….”

A former SS reservist in Sonderkommando 4a, Heinrich Heyer, remembered in a post-war interrogation how “[t]hese SS soldiers … at night, they were delirious and would scream something like ‘Nakolino’ (approximately, in Russian, ‘On your knees!’) or ‘Nagolino.’ I can’t say what this expression meant….”

These words were incomprehensible to Heyer, but they most likely referred to the command that the firing squads learned and gave to their victims: “Kneel down.”

This is only part of the evidence about what happened behind the scenes of these shootings and how the executioners remembered their deeds. The Tragedy of Babyn Yar in German Documents by Aleksandr Kruglov provides further information.

Kyiv Building Superintendent: ‘I Came To The Apartment To Take The Old Woman Out Of It’

Working in the Ukrainian Security Service's archives, we were able to find evidence about Babyn Yar from one Kyiv resident that had not been published earlier.

After the Nazis took over Kyiv, Fedir Lysyuk became the superintendent of several apartment buildings on the city’s Zhylianska Street and, then, on Saksahanskoho Street.

At one of his post-war interrogations, Lysyuk noted that “Building supers had the obligation to make sure that Jews did not remain in their administered buildings and to ensure their attendance at pickup points.

With this goal, I personally went myself by the apartments where Jews were living and checked whether all of them had left, and, in accordance with the directions of the district housing authority, sealed them shut.”

After checking the apartment buildings, Lysyuk put together a list of those Jews who were sick and could not appear at a pickup point.

“In the buildings under my management, there were three sick Jews -- two old women and a man. These people couldn’t get out of bed at all. For that reason, they weren’t able to appear at a pickup point on their own ….”

Lysyuk testified that the sick people from his buildings were picked up a day or two after the shootings at Babyn Yar. However, at another interrogation, he asserted that they were taken 10 days later.

“When the carts came, my role was to organize the people who carried the sick out of their apartments and laid them in the carts ….

When I came to an apartment in order to carry an old woman (Hae Uritskaya– CT) out of it, people then also entered [the apartment] with me who were supposed to carry her out. I suggested to the old woman to get dressed quickly, but she was taking a long time getting dressed. Then I gave the instruction to take her and roll her in a blanket and carry her that way onto the carts. Despite the old woman’s request, I did not allow her to put on a coat …

I did this because, first of all, seeing how the Germans related to the Jews, I had an anti-Semitic attitude. Second of all, I knew that, one way or another, this old woman will be shot by the Germans; and, third of all, I was interested that more clothing and other things remained [in Jewish apartments] since I had plans to use them for myself for profit.”

The shootings continued until November 4, 1943, when Kyiv residents who had not obeyed the Nazi order to evacuate were killed. Two days later, the Red Army retook the city.

Babyn Yar Survivors: How They Saved Themselves

In spite of the thoroughness with which the Sonderkommando participants herded people to the shootings and killed them, several dozen people managed to save themselves at Babyn Yar. Their testimonies allowed the events of September 29-30, 1941 to be reconstructed and charges to be brought against the Nazi perpetrators.

But few people know how these survivors lived during the remaining years of Ukraine’s Nazi occupation and what happened to them later.

After Babyn Yar, Dina Pronicheva, later one of the better-known survivors, hid for a long time with acquaintances and relatives. She frequently moved around, then was arrested as a Jew. She spent a month in Kyiv’s Lukyanivska Prison, and then saved herself again, thanks to a guard’s help.

Pronicheva’s husband, Viktor Pronichev, was not a Jew. He died inside a prison where he had ended up because of a denunciation. Female friends and acquaintances hid the couple’s children, Volodya and Lida.

The brother and sister lived in an orphanage for a long time, including even after the war, when their mother found them. “I remained alone -- naked, barefoot. I sewed myself a coat out of a blanket and went around in it. It was very difficult to take the children since I was living on a starvation diet,” Pronicheva later recalled.

Her fair hair helped save 17-year-old Yevgenia (Genya) Batasheva from Babyn Yar. This is how she described the events of September 29, 1941:

“Many years went by, but I can’t remember that nightmare that took place at the site without being terrified. This was hell in the full sense of this word … the shrieks of the doomed and automatic gunfire; people rushed from one place to another like they were mad; the cries of the doomed and bursts of automatic gunfire merged into a continuous roar. I didn’t quite understand what was happening to me and where I’d lost my mother, sister, and brother.

In this turmoil, I met a 14-year-old girl from our [apartment building’s] courtyard, Manya Palti, with whom I held hands and, together, we started to look for our rescue. We went up to one of the executioners and began to explain to him that we were not Jews and had entirely accidentally ended up at Babyn Yar out of curiosity. He took us to the officers, who were standing near a passenger car, and began to explain something to them.

Soon, one of the Hitlerites indicated to us with a gesture that we can sit in the car, which we did. The chauffeur covered us with some clothes and drove toward the city center .…”

For some time, the girls lived in the family of the Lushchevs, whose daughter, Olya,

was a classmate of Genya’s older sister, Liza. Then, a neighbor, Nikolai Soroka, who was connected with the underground, supplied fake identity documents for Yevgenia and Manya, and helped them to get out of Kyiv.

The way to the frontline was full of new trials and difficulties that are most often not mentioned when the surprising rescue of Genya Batashova is discussed. Through occupied territory, the girls, fearing each man they met -- any of them could betray them-- made it to Kharkiv, where they planned to hide at the house of friends.

But this city also was occupied, and they had to bypass it by foot. They walked for three months until they made it to the Donets River, behind which the frontline ran.

For many, running away from their hometown, from people who knew them before the war, was a reliable escape tactic. Among repatriates’ documents are those of former prisoners of war and civilians who were seized for forced labor in Germany and then returned to Soviet Ukraine.

The State Archives of the Kyiv Region also contain the stories of Jews who voluntarily went to work in the Third Reich to get away from persecution within occupied Ukraine. In 1947, Yevgenia Korobkova wrote to the Soviet Repatriation Commission:

“During the war, I didn’t manage to evacuate in time. At the time of Kyiv's occupation by the Germans, my fate, like that of other remaining residents, was to go to Babyn Yar. I managed to escape from there. I didn’t have long to live at home since a neighbor /someone who was living at the given time in this building/was found who brought the Germans [there] to search for me. I hid and got into Germany …”

Ukrainians And Ukrainian Nationalists At Babyn Yar

The degree to which Ukrainians participated in the events at Babyn Yar -- and, especially, in the executions of September 29-30, 1941 -- is an ongoing topic of research and historical discussion.

In September 1941, the Melnyk faction (named after their leader, Andriy Melnyk) of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) was involved in the creation of occupied Kyiv’s Ukrainian police force. Units of these police took part as auxiliaries in the Nazis’ “big action” at Babyn Yar.

The daily brief of the German armed forces’ 454th Security Division for September 29, 1941 states that "at the request of Kyiv’s city commandant’s office, 300 auxiliary Ukrainian police officers, who had gone through on-site training and were well familiar with Kyiv’s conditions, were placed at the disposal of the 195th Field Commandant’s Office."

These 300 police officers were supposed to be involved in the “big action” beginning that day. The city Commandant’s Office and, before that, the head of the 195th Field Commandant’s Office, Major-General Kurt Eberhard, actively joined in. What kind of people were these?

Contemporary researchers do not equate the “Ukrainian police” with “Ukrainian nationalists.” Members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists served in the police, but, apart from them, the Nazis used Soviet POWs to make up its ranks.

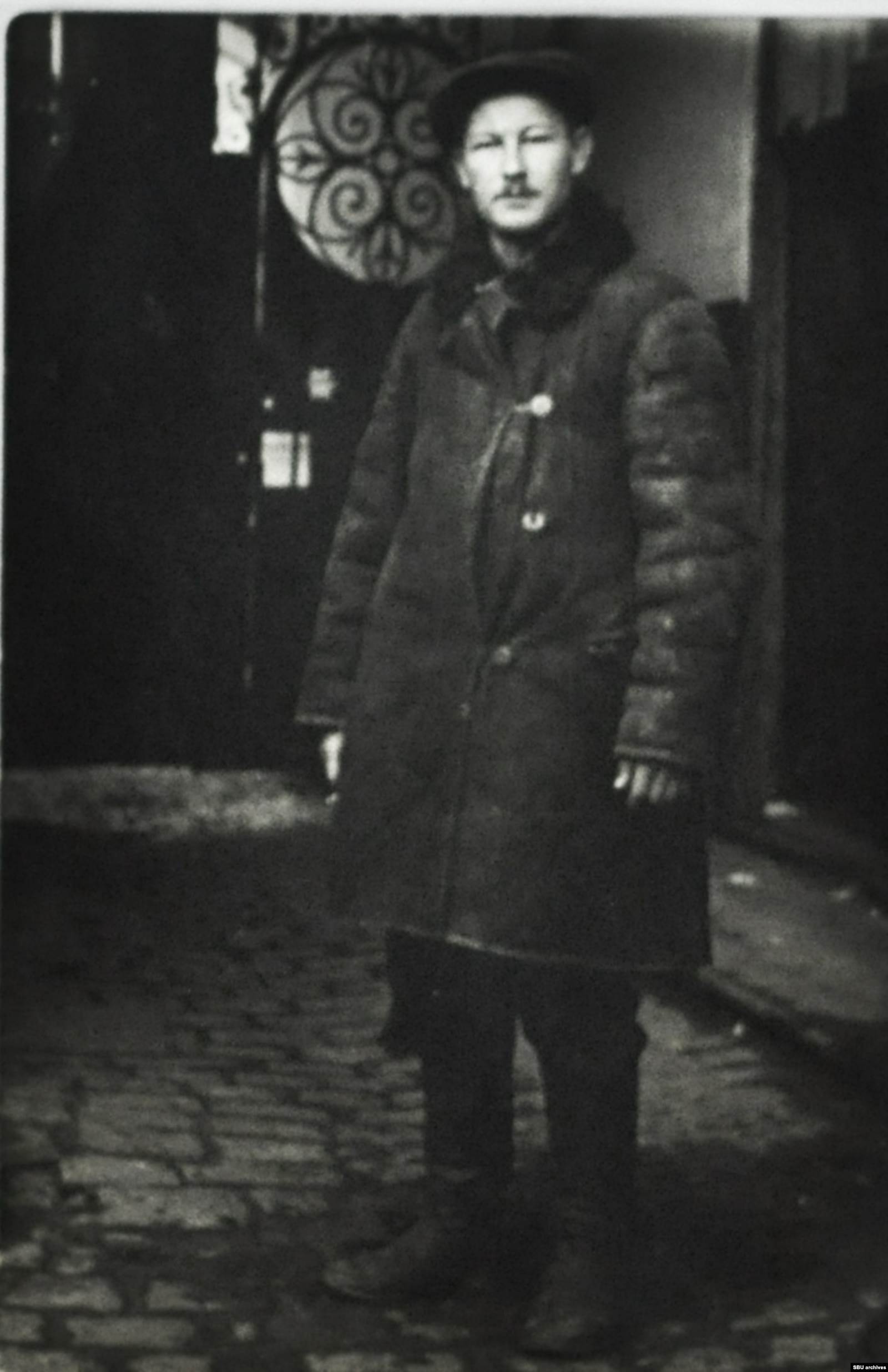

One of the organizers of the police units arrived in Kyiv on September 23, 1941 from Zhytomyr, a city about 140 kilometers (87 miles) to Kyiv’s west. Using the pseudonym Ksenon, the police organizer described the environment from which his subordinates came:

“Bolshevik prisoners made up 75 percent of the regional police garrison. These people were barefoot, in tatters since they were taken out of the prisoner camps, where there was nothing to eat, there was no water, there was nothing to cover yourself with. They slept on straw.”

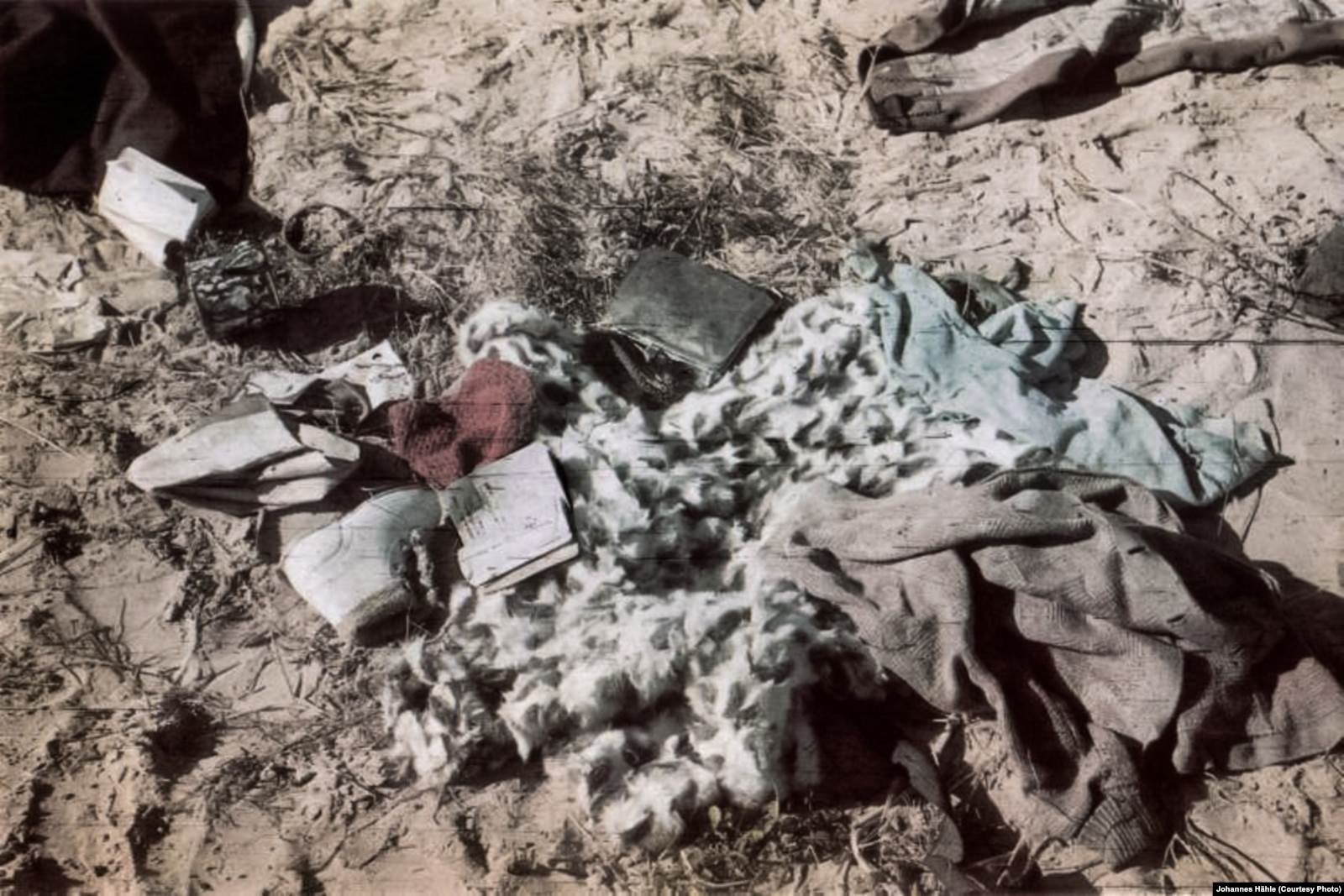

According to the testimony of Sonderkommando driver Fritz Hefer, and also post-war interrogations of police personnel, these local police sorted and preserved the Jews’ clothes and things near the wall of the Lukianivske Cemetery on Simi Khokhlovych Street. The items were taken from people before they were shot.

Some of the police caught Jews on the streets and delivered them to Babyn Yar. But, as the police recounted during their interrogations, they took people captured on the street to a place beyond which it was already forbidden for civilians to go --the intersection of modern-day Illienka and Simi Khokhlovych Streets-- rather than to Babyn Yar itself.

The Sonderkommando led the Jews to the ravine and carried out the shootings. The Germans did not assign highly sensitive work to the Ukrainian police.

One policeman identified as I. Muzir told the State Security Ministry: “….Grigoryev approached the German officer and stated, ‘We, the Ukrainian police, have brought the yids [an offensive term for Jews -- CT].’ At first, the German officer didn’t understand Grigoryev, but a Jewish woman who was standing nearby translated Grigoryev’s words for him. After that, the officer called another German and ordered him to take us further into the field, where everyone (the Jewish prisoners – CT) was undressed ….

When we came to this place, I, Sirosh, Grigoryev, Grishka, and Shcherbina began to undress all the people who walked by. After all the outer clothing had been removed from a person who was passing by, he continued ahead, and we undressed the next ones. After about an hour, a German came up to us and ordered us to stop undressing people and to start loading things into a car.

”People often ended up in the police who had no connection to either the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists or the Red Army-- like, for instance, the policeman F. Sirosh, mentioned by Muzir, who was convicted of speculation [in goods] before the war. As of 1941, he was very short on money with which to feed his wife and two children.

One of the POW police officers was the Kyiv resident A. Stasyuk. He was taken prisoner during the battle between Soviet and Nazi forces over the city – known as “the Kyiv cauldron” -- and consequently joined the police. Stasyuk was not a nationalist. During a post-war interrogation with the Soviet Ukrainian Security Ministry, he described the police as relatively passive participants in Babyn Yar:

“…. When we came to the site, we saw that there was a large square there where a mass of things in a mess were lying. They (the Germans – CT) ordered us all to carry these things to one place and store them. We did this work. When we were picking up the things there, trucks came ….”

Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists member Roman Bida, using the pseudonym Gordon, was also among the police near the Lukianivske Cemetery’s wall.

One V. Alperin testified about this OUN member. In 1991, Alperin published his recollections about how a Ukrainian policeman “with sorrowful eyes,” who was called “Mr. Gordon,” led him, a 5-year-old boy together with his mother and grandmother almost out from under a machine gun outside of Babyn Yar.

Roman Bida helped this family with fake documents and even could get an official order for them to move into another apartment.

Later, “Gordon” worked as the boss of an investigative unit of the Ukrainian city police. The Nazis arrested him in roughly November – December 1941 and executed him.

‘Special Treatment’ And Burning Corpses: How The Syrets Camp Functioned

The shootings at Babyn Yar did not cease in September 1941. Over the following two years, it became the last resting place of not only Jews, but also Romas, intellectuals, Soviet prisoners of war, members of the underground, Ukrainian nationalists, people with intellectual disabilities and mental illnesses, and hostages from among Kyiv’s residents.

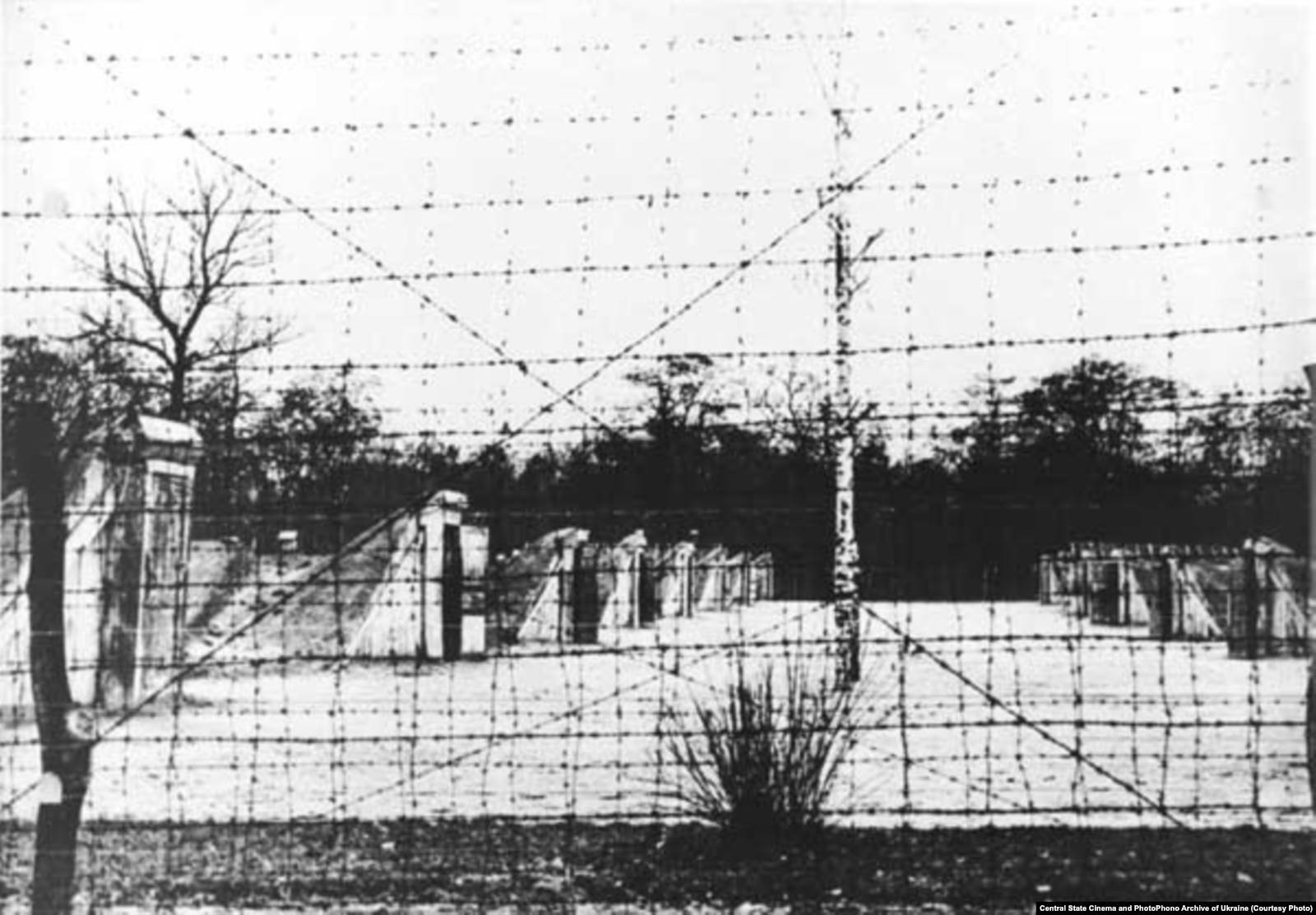

In June 1942, the Syrets correctional labor camp, run by the SD intelligence agency, was set up in the immediate vicinity of Babyn Yar. The surviving inmates of the Syrets camp were the first witnesses whose testimonies the NKVD investigators recorded. One of them, Vladimir Davidov, came into an NKVD regional branch on November 9, 1943 to report “the Germans’ massacre of Kyiv's Jewish population.”

Davidov was the first to tell the brutal history about the murder of Jews in Babyn Yar, and, also, about the Syrets concentration camp. He explained how its prisoners were supposed to excavate and incinerate tens of thousands of corpses from the site of the shootings at Babyn Yar.

In August 1943, a so-called “death squad” of 327 prisoners from Syrets was formed. Shackled in leg irons, the prisoners built “ovens” out of the fencing and tombstones of an old Jewish cemetery located close to Babyn Yar, stacked firewood and the excavated corpses in them, and then incinerated the lot. In one such apparatus, they were destroying 2,000 bodies all at once.

Eighteen of the death squad prisoners managed to survive the war. Among them was Davidov.

As a former NKVD employee, Davidov, who had headed the labor department in the secret police’s Volgostroi construction company before World War II, knew how the Soviet secret service system worked. Possibly for this reason, he was the first of the ex-Syrets prisoners to come and testify:

“…After several days, during the excavation process … we saw a gruesome picture and also smelled the stench of decomposing corpses.

They ordered us to work very fast. They didn’t even let us urinate.

There were tens of thousands of corpses in this pit. There were 2 big spurs in the pit, where there were approximately 50,000 Jewish corpses. Then, at Babyn Yar, there was a pit of the people shot, stretched over half a kilometer (a third of a mile – CT); or more precisely, it was an anti-tank trench. There were killed Red Army commanders there; to be more exact, the command staff. It was possible to see this from the insignia. … In this pit, there were 20,000 people ….”

Vladimir Davidov’s testimony lay at the foundation of the report, which, on November 12, 1943, came into the USSR’s People’s Commissariat for State Security (NKGB). There, for the first time, mention was made of the “100,000 Soviet people, including up to 20,000 Red Army prisoners of war; about the use of (dushegubok) vehicles for killing prisoners [by asphyxiation from exhaust gas], and the use of Syrets camp prisoners to conceal the traces of mass murders at Babyn Yar.”

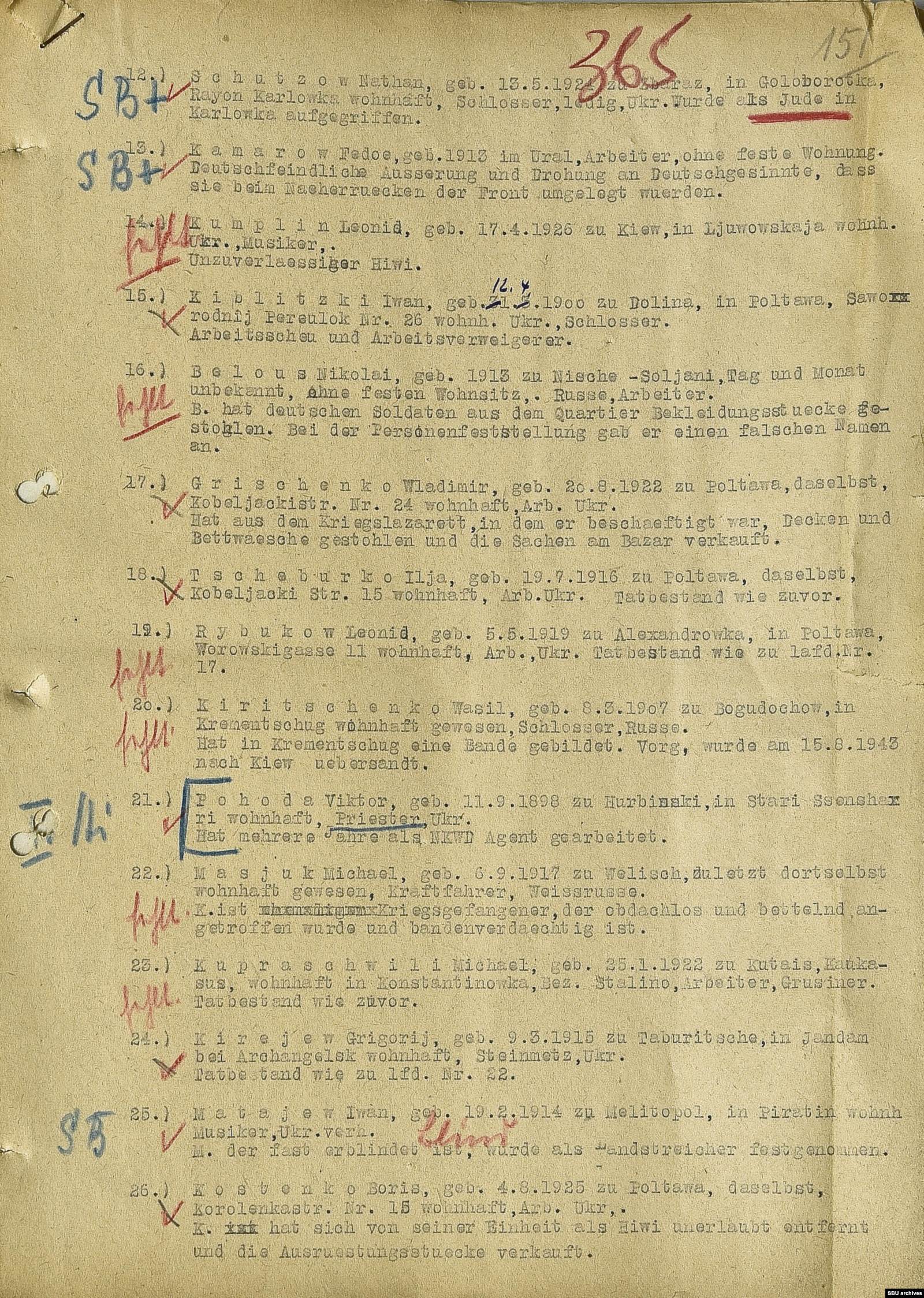

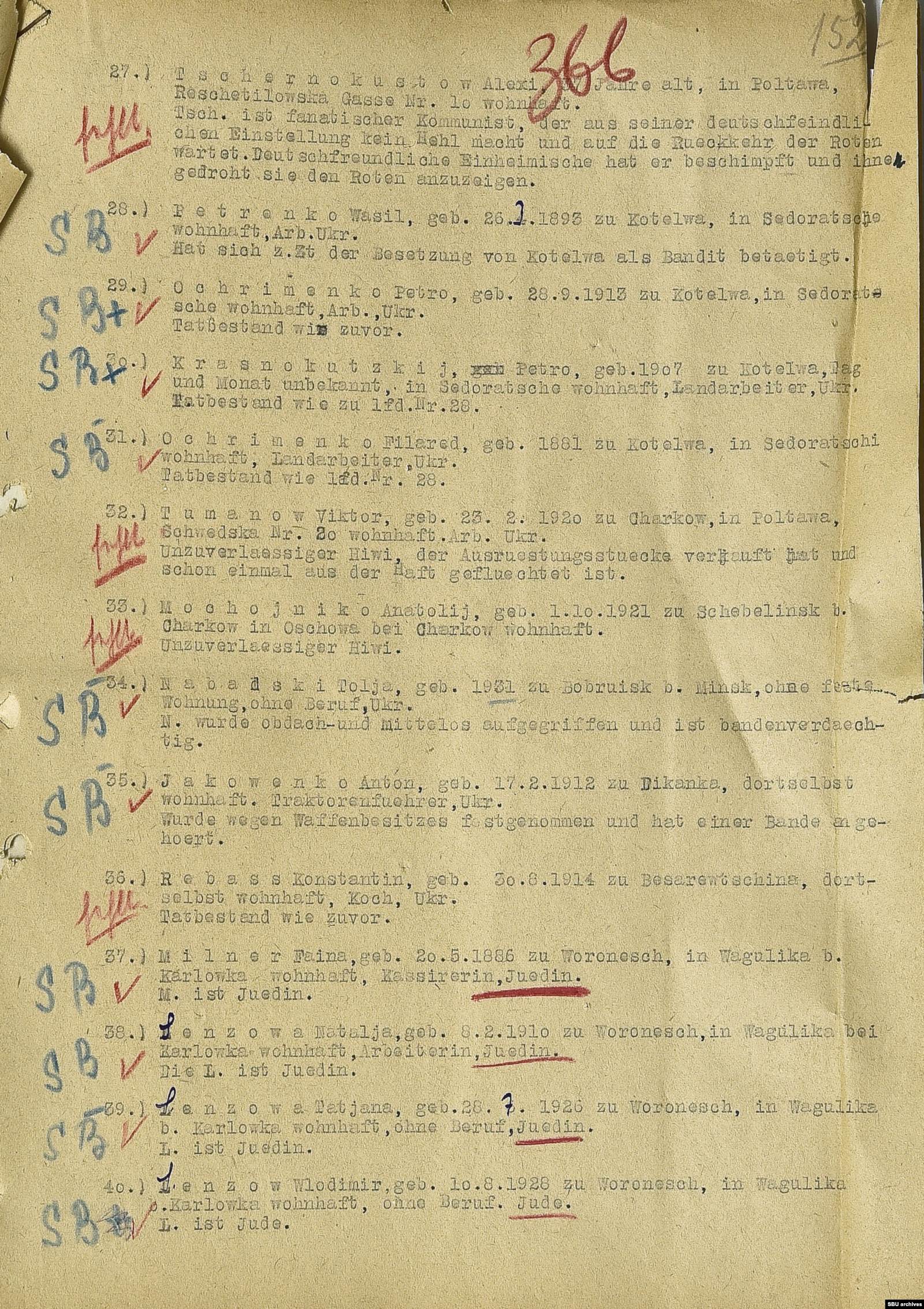

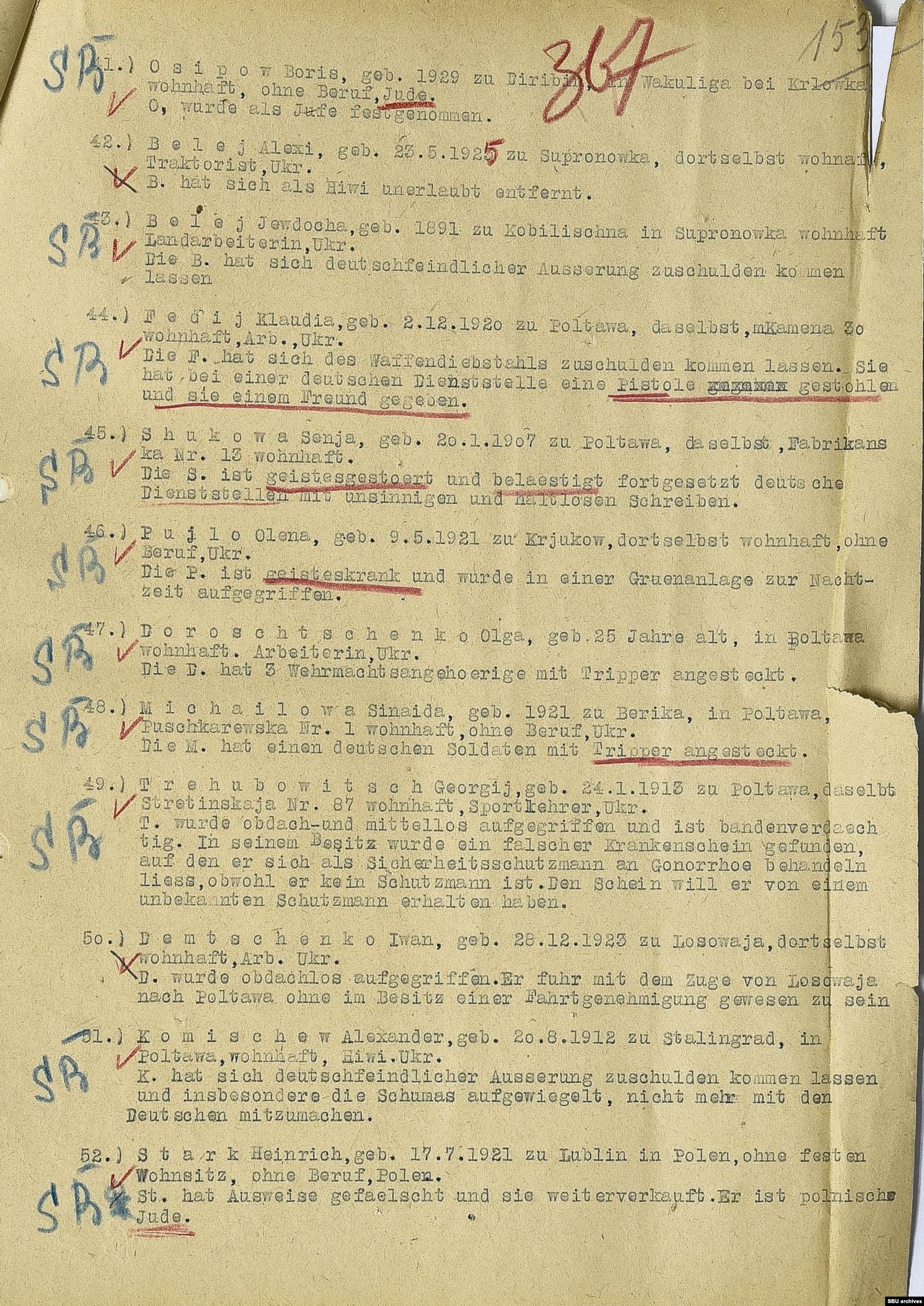

Until recently, it was believed that German documents about the shootings at Babyn Yar had not been preserved. During their work on a book about the Syrets camp, however, the authors of this article managed to find in the Ukrainian Security Service's archives the original of a German report about prisoners who escaped while being transferred on August 24, 1943 from the central Ukrainian city of Poltava to a Kyiv transit camp, called in German a Durchganghaftlager or DHL. As of approximately May 1943, the Syrets camp had such a classification.

On the road to Kyiv, 18 of the 67 prisoners managed to escape. The document is unique because traces of the work of SS officials can be seen on it. These officials decided the fate of the remaining prisoners who were transferred to Kyiv. The last names of 18 of the escapees are marked with “fehlt” (“is missing”) in bright red pencil.

The inscription SB (Sonderbehandlung), in dark blue pencil, is near the majority of these last names. SB signifies “special treatment;” that is, execution. Only several people’s names bear the inscription DHL, signifying their assignment to the Syrets camp.

Among the people who, at the stroke of a blue pencil, were deprived of life and shot at Babyn Yar are a Jewish family; a woman with a mental disorder; Soviet prisoners of war, an itinerate, blind musician; a communist; a priest labeled “an NKVD agent”; escapees from forced labor, and others.

Over two days in September 1941, 33,771 people were killed at Babyn Yar. Within two years, that number had increased to 100,000. -Volodymyr Birchak is an historian and journalist who researches the history of World War II, the 20th century Ukrainian liberation movement, and repressions of Ukrainian clergy. Birchak oversees academic programs at the Center for Research of the Liberation Movement in Ukraine and worked as the deputy director of the Ukrainian Security Service’s archives between 2014 and 2016.

-Tetiana Pastushenko is a senior research associate at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine’s Institute of the History of Ukraine. Pastushenko, who holds a Ph.D in historical sciences, specializes in researching the Nazi occupation of Ukraine, prisoners of war, and civilian victims of World War II in Ukraine.